Artists’ Colony on Hohe Warte

House Moser during the construction phase from the garden, in: Innendekoration, 13. Jg. (1902).

© Heidelberg University Library

House Moll during its construction in 1900, in: Innendekoration, 13. Jg. (1902).

© Heidelberg University Library

Villa Moser-Moll, on the right the house Moll, on the left the house Moser, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 9. Jg. (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

In early 1900, the Hohe Warte, a hilly plateau in the 19th District of Vienna, became the site of an ambitious Secessionist building project in keeping with the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art]. The architects in charge were Joseph Maria Olbrich and subsequently Josef Hoffmann. The villas that formed part of the artists’ colony were inhabited by the families Moll, Moser, Spitzer, Reininghaus and Henneberg.

As early as 1896, Olbrich had devised a plan for a villa quarter on the Cobenzl (Krapfenwaldl), but this project was never implemented. Olbrich subsequently moved to Darmstadt, where he was able to realize his ambition with an artists’ colony on the Mathildenhöhe. Josef Hoffmann would eventually realize Olbrich’s dream in Vienna, too, building an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, after Secessionists like himself, Moll, Moser and others, had managed to buy a large plot of land with building permission that was suitable for a villa colony.

Carl Moll’s efforts, especially, were likely instrumental for the project’s realization. In 1900, he received Olbrich’s plans for the intended settlement on Hohe Warte, which no longer exist today. Olbrich himself had lost interest in any active participation in the project, and handed the reigns over to his colleague Josef Hoffmann. A total of four villas were erected as part of the scheme.

The individual artists’ homes were to show strict stylistic cohesion through the use of white plaster, blue timber framework and red tiled roofs. The interiors were dominated by the color white in conjunction with ornaments in signal colors, such as blue, red, yellow and green. The prevalent design principles were square shapes, clear lines and symmetry. The aim was not to create uniform terraced houses, but rather to combine heterogeneous building styles to create a homogeneous and harmonious overall impression. It was only through the addition of later buildings, not commissioned by artists, that this stringent cohesion was loosened in favor of individual solutions.

Villa Moser-Moll

The first building project to be completed was the double residence for the families of the artists Moser and Moll. The villa, situated at Steinfeldgasse 6/corner of Geweygasse 13, was divided into two separate homes. On the left side was Moll’s house, while Moser’s was situated on the right, in close proximity to Friedrich Spitzer. Completed in 1901, the double home was the first villa to espouse the artists’ colony’s design principles. The building project was a matter that was especially close to Carl Moll’s heart. Time and again, he captured the villa – both the interior and exterior – and the environs on Hohe Warte in his paintings and woodcuts. For a considerable time, views of his home even adorned his letterhead. By using the building as a motif for his art, he invested the concept of a virtuosic Gesamtkunstwerk with yet another nuance.

Villa Moser-Moll

Villa Spitzer, back with garden, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, 4. Jg. (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Villa Spitzer

The neighboring plot at Steinfeldgasse 4 belonged to Friedrich Victor Spitzer. The sugar industrialist and amateur photographer was part of the circle of friends surrounding Carl Moll, Gustav Klimt and Hugo Henneberg, who regularly came together at Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon. As a portrait photographer, he captured not only Klimt but also Ferdinand Hodler who, during his stay in Vienna in 1904, resided at Spitzer’s villa. The design principles of Villa Spitzer were largely aligned with those of Villa Moser-Moll, with square and rectangular structures dominating its appearance. This principle even extended to the gardens of the villas. The furnishings of Spitzer’s villa were not designed exclusively by Hoffmann, as the designer also incorporated items of furniture by Olbrich, which Spitzer had moved from his city apartment. A layout plan informs us about the distribution of the rooms. Intended for one person, the residence included not only living areas, guest rooms and staff quarters but also a photographic studio and darkroom on the first floor, where Spitzer was able to work.

Villa Spitzer

Villa Henneberg, garden side left, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 9. Jg. (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Villa Henneberg

The married couple Hugo and Marie Henneberg owned the plot at Wollergasse 8. On this site, Hoffmann erected the largest of the three early artists’ villas in 1900/01. Like Spitzer, Henneberg, too, was a keen amateur photographer who often presented his photographs at exhibitions of the Secession. The Hennebergs’ villa stood out from the others on account of its lavish, rambling garden. The ornamental structures on the facade were greatly reduced compared to those of the Moser-Moll and Spitzer villas, boasting only a reticent timber framework pattern on the top of the pediments. The building was structured through overlapping, geometrical components. Extant layout plans show us the disposition of the villa’s rooms. Along with several bedrooms and a sprawling dining room for social gatherings on the ground floor, Henneberg had an office and a photographic studio fitted in the attic.

Villa Henneberg

House Moll 2

© Bildarchiv Foto Marburg

Villa Hochstetter

© Bildarchiv Foto Marburg

Villa Ast, view of the walkway, in: Moderne Bauformen. Monatshefte für Architektur und Raumkunst, 12. Jg. (1913).

© Heidelberg University Library

Bruno Reiffenstein (?): Insight into the Villa Ast, circa 1912, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, 13. Jg. (1912).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Carl Reininghaus Makes Room for Ast and Moll

The fifth investor of the artists’ colony building project was the patron of the Secession Carl Reininghaus. Josef Hoffmann had planned a villa to be built on his plot as well. For unknown reasons, however, these plans were never realized. At the “Beethoven-Ausstellung” [“Beethoven Exhibition”] held in 1902 at the Secession, Reininghaus had bought Klimt’s The Beethoven Frieze (1901–1902, Belvedere, Vienna), reportedly with the aim of incorporating it into an as yet unexecuted building. In a letter to Maria Zimmermann, Klimt wrote in 1902:

“the house where they [NB: the panels of The Beethoven Frieze] are supposed to go has not been built yet – it hasn’t even been started [...] plenty of time for the man to regret his purchase – ”

The house in question might have been the intended villa on Hohe Warte. While incorporating a Klimt frieze into the villa would have fitted in well with the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, there is no concrete evidence to suggest that this was indeed the plan.

The fact that the Reininghaus plot remained empty ushered in the villa colony’s second building phase. In 1906/07, the site was used to erect a residence for Carl Moll, known as “Haus Moll,” at Wollergasse 10. Between 1909 and 1911, another building, Villa Ast, at Steinfeldgasse 2, was built for the family of the industrialist and art patron Ast. Moll subsequently bought the latter villa for his stepdaughter Alma Mahler-Werfel, who would live there with her third husband, Franz Werfel, from 1932, hosting a well-attended salon for artists and musicians.

In 1905/06, Josef Hoffmann built villas in immediate proximity to the artists’ colony for Alexander Brauner, an industrialist, and Helene Hochstetter, who was related by marriage to the art patron Karl Wittgenstein. The styles of the four later buildings deviated from the cohesive appearance of the earlier villas, tracing Josef Hoffmann’s personal stylistic evolution. The interior decoration was executed by the Wiener Werkstätte under Hoffmann’s guidance.

Klimt and the Artists’ Colony

Carl Reininghaus was not the only one who had planned to integrate paintings by Klimt into the overall design of his villa on Hohe Warte. Both the Henneberg and the Ast families owned works by Klimt, which Hoffmann skillfully incorporated into the concept of his Gesamtkunstwerk villas. In the hall of Villa Henneberg, for instance, Hoffmann gave Klimt’s painting Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt – Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)) pride of place. Positioned above a fireplace, and flanked by two slender glass cabinets with Asian porcelain, the portrait appeared almost like an altarpiece. At “Haus Ast,” the building owner devoted an entire room to Klimt’s work Danaё (1907/08, private collection). The painting was hung in the oval ladies’ salon on a wall made from gray-green Cipollino marble, against which Klimt’s gold ornamentation stood out to great effect. Additionally, the work was positioned directly within the opening of the door, so that it would be visible from the dining room.

The houses of the artists’ colony were united not only by their uniform appearance but also by the close friendships between their residents, which helped the quarter gain a special status. Friendly artists were regularly invited to gatherings at the villas of Moll, Moser, Henneberg and Spitzer. The Secessionists met their supporters and commissioners there. Their homes were places of encounters and intellectual exchange. Klimt, too, was a regular guest at the villas on Hohe Warte.

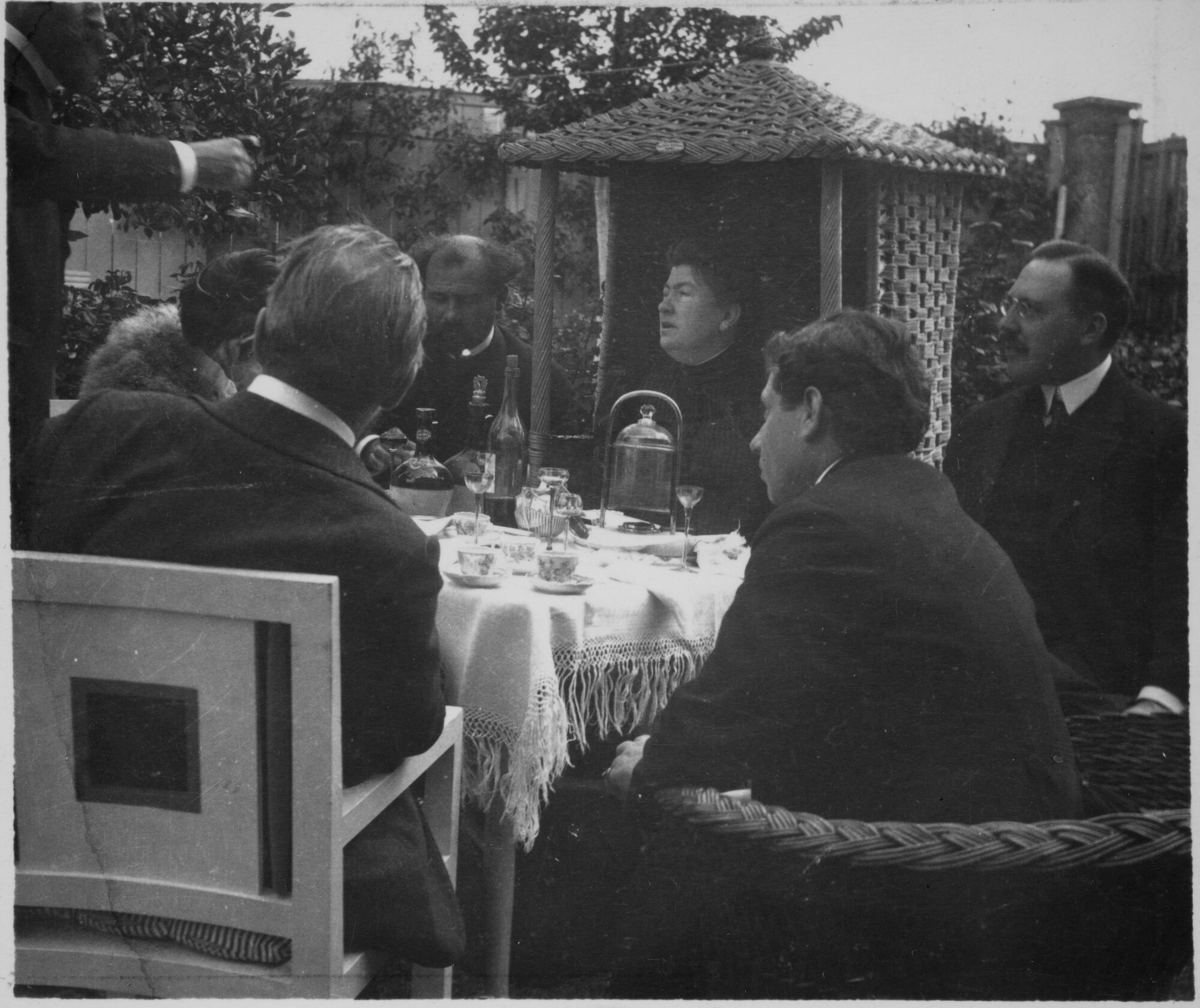

Gustav Klimt in company in the garden of Villa Moll on the Hohe Warte, May 1905, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Photographs taken in 1905, for instance, show Klimt, Alfred Roller, Josef Hoffmann, Gustav Mahler and others together in the garden of Villa Moll. The villa was likely not only a place for social gatherings but also for more or less official work meetings between members of the Secession and perhaps also the Kunstschau group. Klimt wrote to Emilie Flöge in this context:

“Moll has sent me a telegram asking me to have a meeting with him tonight out at his place – I will have to go whether I like to or not, as I don’t know what it is about”

Thus, the artists’ colony had fulfilled its original purpose of providing a place of collaborative work for like-minded artists.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hohe Warte. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hohe_Warte (05/18/2020).

- belvedere. werkverzeichnisse.belvedere.at/online/text/355447/koloman-moser/biography (05/18/2020).

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Gerd Pichler, Joseph Maria Olbrichs nie gebaute Künstlerkolonie in Wien und Josef Hoffmanns Künstlerkolonie auf der Hohen Warte.. journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/icomoshefte/article/view/46883/40388 (05/18/2020).

- Markus Kristan: Josef Hoffmann. Villenkolonie Hohe Warte, Vienna 2004.

- Amelia Sarah Levetus: Die Villa Ast in Wien von Professor Josef Hoffmann, in: Moderne Bauformen. Monatshefte für Architektur und Raumkunst, 12. Jg. (1913), S. 1-24.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Villach (17.10.1902). S63/28.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Wien (undated). Autogr. 959/54-6, .