Hugo Henneberg

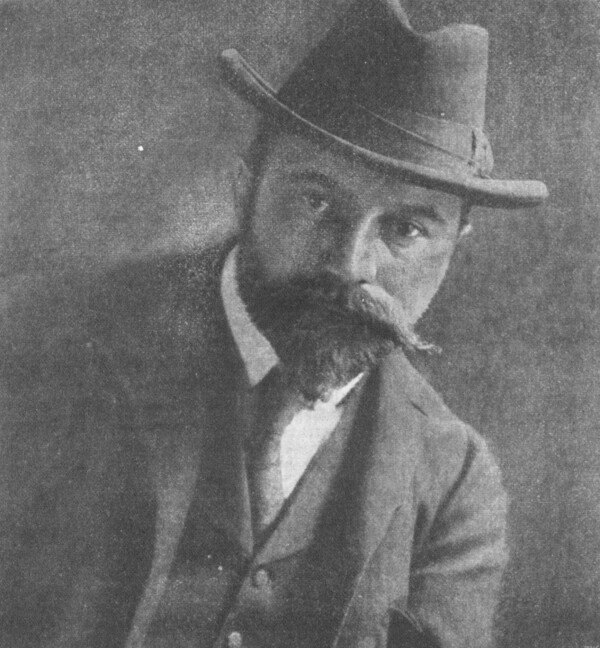

Hugo Henneberg photographed by Ludwig David, 1901, in: Österreichische Illustrierte Zeitung, 31.03.1912.

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Villa Henneberg, studio, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, 4. Jg. (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Insight into the Villa Henneberg, circa 1903

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

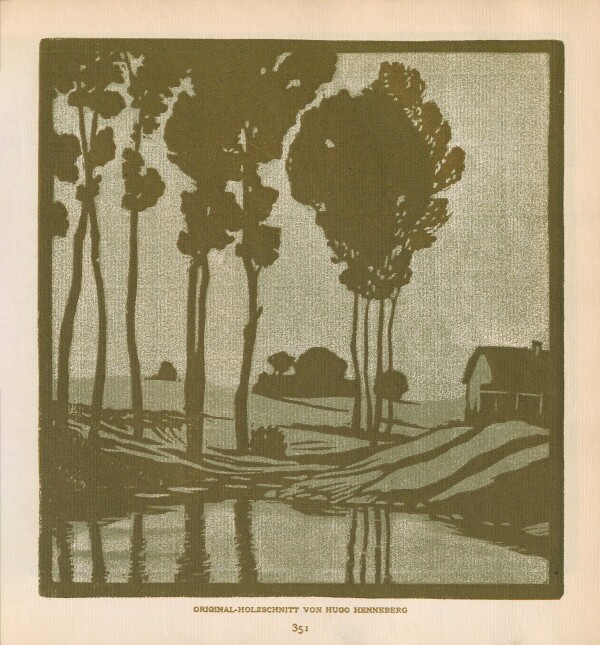

Color woodcut by Hugo Hennberg, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Heft 21 (1903).

© Heidelberg University Library

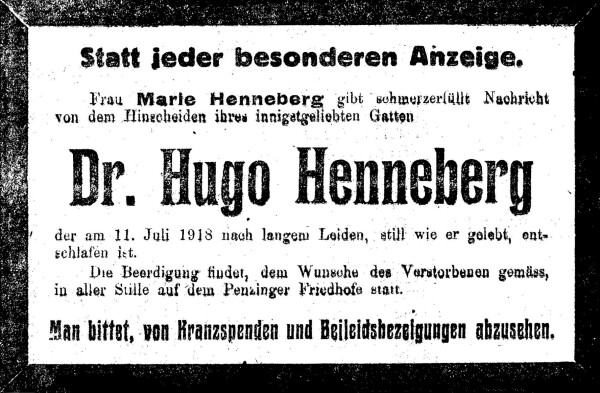

Death notice of Hugo Henneberg, in: Neue Freie Presse, 13.07.1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Hugo Henneberg was one of the leading art and landscape photographers in Vienna around 1900 and a representative of Pictorialism. Together with Heinrich Kühn and Hans Watzek he formed the artists’ association Trifolium, which also exhibited at the Vienna Secession. In 1901/1902, Gustav Klimt created a portrait of Hugo’s wife Marie Henneberg.

Hugo Henneberg, born in 1863, studied physics, chemistry, astronomy and mathematics at the universities of Vienna and Jena. He earned his PhD in physics in 1888. He then went on extended travels, for instance visiting the US, Greece and Egypt.

Career of an Amateur Photographer

Henneberg developed an intense interest in photography during his studies. He participated in exhibitions as an amateur photographer from the 1890s. Henneberg, a gentleman of independent means, also joined associations such as the Club of Viennese Amateur Photographers (1891), The Linked Ring (1894) as well as later the Vienna Photo Club (1903).

At the Club of Viennese Amateur Photographers – later also known as Vienna Camera Club – Henneberg met the physician Heinrich Kühn and the painter Hans Watzek. Together they founded the artistic photographers’ association Trifolium in 1897 and developed a new technical process for gum prints. The artists’ magazine Camera Work honored the achievements of the three amateur photographers in 1906, writing:

“They mastered this process in every sense, and developed it by endless experiments, the value of which, at that time, they themselves hardly realized; but these led to the invention of the multiple gum-print employed by the Austro-German photographers, which is […] the most important printing process at present at the disposal of the artists amongst the photographers.”

Henneberg initially presented the first works created with this new printing technique at the Vienna Secession in 1902; he later also exhibited the works in New York – with the help of the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, with whom he corresponded regularly over several years.

A Journey and a Klimt Painting

There were not only professional, but also many private links between Gustav Klimt and Hugo Henneberg: The Hennebergs as well as Klimt joined a group surrounding the Moll family for a journey to Italy in the spring of 1899. Alma Mahler-Werfel, Carl Moll’s stepdaughter, in her diaries for instance recalled a shared cold lunch in Venice. A photograph taken there and dated 2 May 1899 shows Alma Mahler-Werfel and her sister Grete Schindler as well as the artists Carl Moll, Josef Engelhart, Hugo Henneberg and Gustav Klimt.

A few years later, Klimt painted the Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale). The work – then still unfinished – was presented for the first time at the Vienna Secession in 1902. In 1903, the magazine Das Interieur published several interesting photographs that showed Klimt’s painting and the interior decoration of the great hall of the newly built Villa Henneberg. The Hennebergs had commissioned the architect Josef Hoffmann to design their multi-storey residence with its own photo studio in the attic in the 19th District of Vienna – in the “Künstlerkolonie,” an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, where Hugo’s friends and fellow artists Carl Moll, Kolo Moser and Friedrich Viktor Spitzer lived as well.

Graphic Works

Henneberg focused on his work as a graphic artist after 1900 and for instance published a Wachau Portfolio and a Dürnstein Portfolio of art prints. Several of his colored woodcuts, which primarily depicted city views and natural landscapes, were also published in the magazine Ver Sacrum. A reporter commented on Henneberg’s graphic oeuvre, which was at the time being presented at the Secession’s spring exhibition, in the Wiener Abendpost in 1919:

“[…] Dr. Hugo Henneberg, much esteemed as an artistic photographer, to everyone’s surprise has left colored landscape woodcuts created by himself which have never been shown before and which belong to the finest works of the greatest artistic value that have surfaced locally in this segment in the last decade.”

Henneberg had died after an illness in 1918, only a few months after Gustav Klimt. The artist and photographer, who was described by his contemporaries as a humble person, had “furthered the development of artistic photography in the most meritorious manner and […] created exemplary photographs,” as a brief acknowledgment in the journal Photographische Correspondenz explained. According to his obituary in the Neue Freie Presse, Henneberg was buried at the cemetery in Vienna-Penzing, 14th District.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hugo Henneberg. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hugo_Henneberg (04/20/2020).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Hugo Henneberg. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/Henneberg_Hugo (04/20/2020).

- Fritz Matthies-Masuren (Hg.): Gummidrucke von Hugo Henneberg, Heinrich Kühn und Hans Watzek, Halle (Saale) 1902.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hoffmann Häuser. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hoffmann-Häuser (04/20/2020).

- Alfred Buschbeck: Das Trifolium des Wiener Camera-Clubs: Hans Watzek. Hugo Henneberg. Heinrich Kühn, in: Die Kunst in der Photographie, 2. Jg. (1898), S. 17-24.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 581-582.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 273.

- Camera Work. A Photographic Quarterly, Heft 13 (1906), S. 21-28.

- Joseph August Lux: Villenkolonie Hohe Warte. Erbaut von Prof. Joseph Hoffmann, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, 4. Jg. (1903), S. 121-183.

- Astrid Mahler: Liebhaberei der Millionäre. Der Wiener Camera-Club um 1900. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Fotografie in Österreich. Band 18, Vienna 2019.

- Felix Czeike (Hg.): Historisches Lexikon Wien, Band 3, Vienna 1994, S. 142.

- Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Hg.): Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950, Band 2, Vienna 1994.

- Walter de Gruyter (Hg.): Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon. Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, Band LXXI, Berlin 2011, S. 509.

- Hans Vollmer (Hg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Begründet von Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker, Band XVI, Leipzig 1923, S. 391.

- Christian Philipsen, Thomas Bauer-Friedrich, Wolfgang Büche (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und Hugo Henneberg. Zwei Künstler der Wiener Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale) (Halle (Saale)), 14.10.2018–06.01.2019, Cologne 2019.

- Anthony Beaumont, Susanne Rode-Breymann (Hg.): Alma Mahler-Werfel. Tagebuch-Suiten. 1898–1902, 2. Auflage, Frankfurt am Main 2011, S. 249-250.

- Photographische Correspondenz, 60. Jg., Nummer 694 (1918), S. 250.

- Neue Freie Presse, 13.07.1918, S. 13.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 94-97.

- Die Zeit, 13.07.1918, S. 4.

- Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 17.06.1919, S. 2.