Georg Klimt

Georg Klimt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Georg Klimt: Brass company sign

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

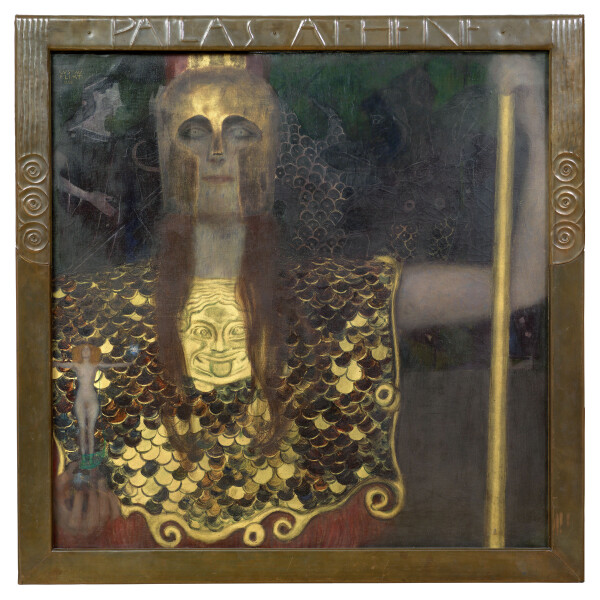

Gustav Klimt: Pallas Athene, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Georg Klimt: Chronicle of the life of the Klimt family, 1924, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Georg Klimt in front of his studio in Neulinggasse

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Georg Klimt, the younger brother of Ernst and Gustav Klimt, worked as an independent metal sculptor and artisan and taught at the Art School for Women and Girls in Vienna. He compiled an extensive chronicle of the Klimt family, which is now owned by the Klimt Foundation.

Georg, the younger brother of Gustav and Ernst Klimt, was born in Vienna in 1867. After an apprenticeship, he followed in his brothers’ footsteps and attended the Arts and Crafts School of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna (now the University of Applied Arts Vienna). The institution’s monthly periodical Kunst und Kunsthandwerk reveals that several of the metalworks and goldsmithing works he created as a student were publicly exhibited. He married in 1901 and began working as an independent artisan after completing his education. He soon also started to teach “artistic metalcraft” at the Art School for Women and Girls.

Collaboration with Gustav Klimt

Georg Klimt repeatedly worked with and for his brother Gustav: He posed for several of Gustav’s works, including the ceiling paintings in the Burgtheater, as documented in photographs. Georg Klimt later also contributed to the decorations of Dumba Palace and executed his brother’s designs for the metal frames of the paintings Pallas Athene (1898, Wien Museum, Vienna) and Judith I (1901, Belvedere, Vienna). Furthermore, Gustav Klimt recommended his brother to artists of the Vienna Secession. Georg Klimt’s collaboration with Joseph Engelhart is for instance mentioned in the exhibition catalogue of the “4th Art Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists.”

“The Life of Gustav Klimt and his Family”

Georg Klimt’s chronicle Das Leben des Gustav Klimt und seiner Familie (1919–1924, Klimt Foundation, Vienna) is of major significance for scientific research on Gustav Klimt’s life and work. The chronicle is mentioned as early as 13 January 1929 in an article in the newspaper Neues Wiener Journal, in which the journalist Leopold Wolfgang Rochowanski recounts his visit to Georg Klimt’s studio in Vienna’s 3rd District:

“Georg Klimt’s main concern is to correct all the false statements, all the misrepresentations that have been propagated, the many smaller and greater errors in books and essays on his brother, and to capture the truth. […] For a long time, he has dedicated himself to recording all his memories in writing. For this purpose, he has created a splendid book whose cover is decorated with metal and silver ornaments he has embossed himself.”

The article also reveals that the notes on family history in calligraphic writing were illustrated with many private photographs. It goes on to announce that the chronicle would not (yet) be made accessible to the public, but would remain in the family’s possession for the foreseeable future.

The “Forgotten” Klimt?

Only very few sources shed light on Georg Klimt’s life and career: He taught at the Vienna Ladies’ Academy and School for Free and Applied Arts (formerly the Art School for Women and Girls) until the 1920s. His works, such as a brass repoussé altar for a monastic church that he created together with Karl Holey, are mentioned only rarely in newspapers and magazines.

According to the 1929 newspaper article Intimes von Gustav Klimt, Georg Klimt owned reproductions of works by Gustav Klimt as well as furniture from his deceased brother’s studio. He also kept many of Gustav Klimt’s postcards and documents, such as the official letter regarding the Imperial Award (Klimt Archives, Albertina, Vienna) he received for the watercolor Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888/89, Wien Museum, Vienna).

Georg Klimt, who went blind after a stroke in 1930, is thought to have lived in very poor conditions together with his wife for the last few years of his life. This is evidenced by an unaddressed letter now preserved in the archives of the Austrian Gallery Belvedere. In the letter, the director of the Vienna Ladies’ Academy and School for Free and Applied Arts asked for donations to support the former art teacher. Nothing is known about the results of the campaign.

Georg Klimt died in September 1931. His estate comprised a great number of drawings by his brother Gustav, which Georg Klimt’s widow Franziska, née Prachersdorfer, bequeathed to the city of Vienna upon her death in 1943, since there were no direct descendants. These more than 270 drawings are now in the collection of the Wien Museum and currently constitute the world’s largest collection of Klimt’s drawings.

Literature and sources

- Neues Wiener Journal, 13.01.1929, S. 18-19.

- Die Zeit, 01.09.1903, S. 7.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942, S. 14, S. 19, S. 30.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 563, S. 576.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 204, S. 212, S. 245.

- Wolfgang Born: Der Metallbildhauer Georg Klimt. Ein Bruder Gustav Klimts, in: Die Bühne. Wochenschrift für Theater, Film, Mode, Kunst, Gesellschaft, Sport, 6. Jg., Heft 243 (1929), S. 16.

- Felix Czeike (Hg.): Historisches Lexikon Wien, Band 3, Vienna 1994, S. 533-534.

- Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Hg.): Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950, Band 3, Vienna 1994.

- Hans Vollmer (Hg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Begründet von Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker, Band XX, Leipzig 1927, S. 503-504.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Zum Gemälde »Pallas Athene« von Gustav Klimt, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 21. Jg., Heft 147 (1976), S. 8-11.

- Brief von der Wiener Frauen-Akademie an Unbekannt, Jänner 1930, .

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 13.

- Chronik über das Leben der Familie Klimt, "DAS LEBEN DES GUSTAV KLIMT UND SEINER FAMILIE" (1924). S16/1.

- Sterbebuch 1928/36 (Tomus 41), röm.-kath. Pfarre Landstrasse - St. Rochus, Wien, S. 95, Nr. 107.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 8 (1898), S. 24.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Katalog der IIII. Kunstausstellung der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 18.03.1899–31.05.1899, Vienna 1899, S. 26.

- Trauungsbuch 1901 (Tomus XXIII), röm.-kath. Pfarre Rennweg - Maria Geburt, Wien, fol. 130.

- Patrick Werkner: Georg Klimt’s Pallas Athena: The Youngest Goddess of the Wiener Moderne, in: Belvedere Research Journal, Nummer 2 (2024), S. 58-76.