Emil Pirchan

Emil Pirchan in his Munich studio, around 1912

© Steffan / Pabst Collection, Zurich

With his modern, expressionistic designs, the Universalkünstler [universal artist] Emil Pirchan, who was active as an architect, commercial artist, set decorator and author, made a lasting and revolutionary impact on our understanding of graphic art and decor. His monographs on Gustav Klimt and Hans Makart provide an important foundation for current research.

Emil Pirchan was born on 27 May 1884 into a Bohemian family in Brünn [now Brno]. His father Emil Pirchan sen. was a painter who had studied under Carl Rahl and worked as a drawing teacher to Count Salm-Reifferscheidt. His mother Karoline was the daughter of a wealthy local textile manufacturer. Emil Pirchan and his younger sister Elsa grew up in a highly cultured environment, with their parents hosting a salon that was frequented by artists and musicians. When they were a little older, they made use of their maternal grandparents’ box at Brünn City Theater. This is where Pirchan discovered his love for the theater, for which he later worked as a set designer. He also showed an aptitude for writing from an early age. He wrote poems, little stories, plays and a short autobiography. After graduating from high school in 1902, he embarked on a study trip to Italy, before moving to Vienna.

In 1903, he passed the entry examination to the Imperial-Royal Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied architecture under Otto Wagner for three years. During this time, the young artist frequented the coffee house Café Museum. There, he met the artists of the Secession, including Josef Maria Olbrich, Alfred Roller, Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann, who was his second cousin.

Emil Pirchan: Design for a country house, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 14. Jg. (1908).

© Heidelberg University Library

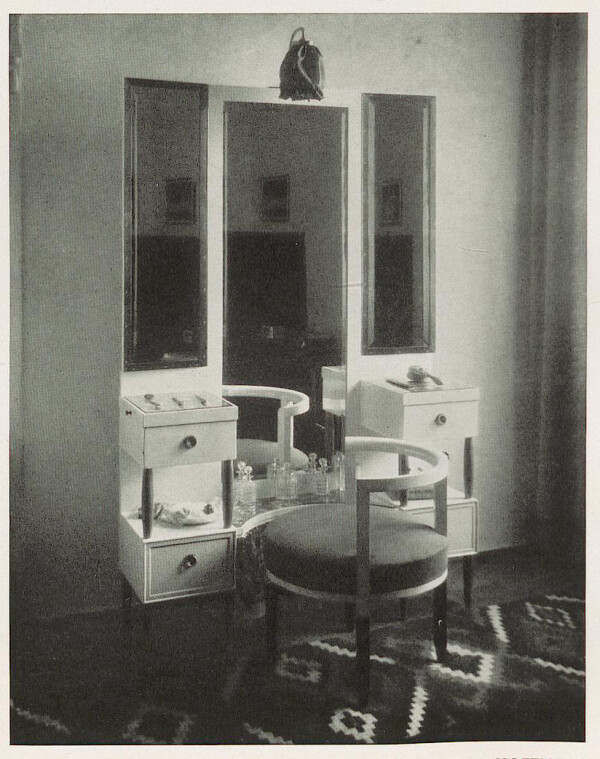

Emil Pirchan: Toilet table, in: Innendekoration, 24. Jg., Heft 12 (1913).

© Heidelberg University Library

Commercial Art, Set Design and Teaching Activities

Despite receiving several awards during his studies, the artist did not enjoy professional success straight away. Pirchan initially returned to his hometown Brünn as a drawing teacher. He also continued to write, took on various small commissions and was a member of the artists’ group Die Scholle. Pirchan’s luck changed when he moved to Munich in 1908 to open up his own architectural studio. Along with planning several single-family homes and apartment units, Pirchan was especially successful as a commercial artist. His commissioners included the artists’ collective Die Brücke, Klavier D. J. Bosman, dancers, as well as numerous bookshops. This success led to Pirchan opening his own art school for commercial art and set design in 1913. That same year, he married Johanna “Hanny” Diehl, the daughter of the late personal physician to Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria.

Along with posters, Pirchan also designed numerous stage sets. He wrote about himself:

“I am hopelessly devoted to the theater, I have lost my brush and pen, heart, mind and hand to it […] I am not only a stage designer […] but an earnestly solicitous servant to the Gesamtkunstwerk of the theater.”

Initially, his Gesamtkunstwerk designs were deemed too impractical to be realized. Instead, he presented them in 1912 in an exhibition at Galerie Tannhauser, where they were well received by the public. It wasn’t until after the War that he was appointed in 1919 as head of set design to the Bavarian State Theaters in Munich under its director Bruno Walter. He subsequently went to Berlin to work under Leopold Jessner, furnishing the stage decorations for several hundred theater productions not only in his new home Berlin but also for international theaters. In 1931, he took over the stage design class at the German Academy for Music and Performing Arts in Prague. Only two years after taking on this position, he sought to be transferred to Vienna. His wish was granted in 1936. Pirchan was appointed associate professor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and became a set designer for the recently opened Burgtheater and Akademietheater. He further acted as director of a newly founded master school for set design. He moved back to the imperial capital and became an Austrian citizen.

Emil Pirchan and the Theater

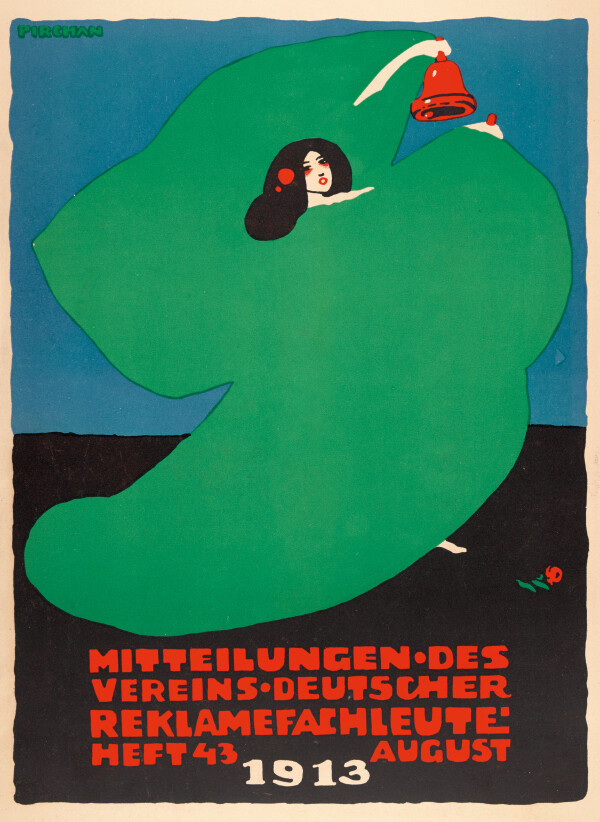

Emil Pirchan: Title page of the "Mitteilungen des Vereins Deutscher Reklamefachleute", issue 43, August 1913

© Steffan / Pabst Collection, Zurich

With his expressionistic designs, Pirchan made a lasting and revolutionary impact on our understanding of theater staging and graphic art. Through his teaching activities – for which Pirchan received numerous awards – he passed his knowledge on to the following generation.

Pirchan as an Author

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, demand for commercial art plummeted. Pirchan, who had abruptly lost his primary source of income, increasingly focused on his writing. In 1914, he published his play Das Teufelselixier [The Devil’s Elixir], followed by his first novel Der zeugende Tod [The Siring Death], which came out in 1918. The artist had furnished his own illustrations for both publications. He further issued a bibliophile periodical, called EOS, which was also successful. Most of his publications were characterized by an elaborate graphic design, with Pirchan even coloring some special luxury editions by hand.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Universalkünstler had another fruitful literary period. Once again occasioned by a lull in his activities as a graphic designer and set decorator – this time on account of his professorship at the Academy – Pirchan wrote a series of monographs on artists and dancers. During World War II, he published works about Fanny Elssler and Therese Krones, followed in 1942 by a Makart biography and the publication Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien [Gustav Klimt. An Artist from Vienna].

Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

A Gustav Klimt Monograph

Following Max Eisler’s comprehensive Klimt monograph, published in 1920, which focused on the artist’s oeuvre, Pirchan wrote about Klimt’s personal sphere. The Universalkünstler, who was acquainted with Klimt from his time at Café Museum, combined a factual reporting style with an anecdotal and novel-like narration. These anecdotes stemmed from his own recollections and from numerous sources among Klimt’s circle, with intimate details divulged not only by Klimt’s friends and fellow artists Rudolf Bacher, Moriz Nähr, Carl Moll and Michael Powolny, but also by his immediate family. His niece Helene Donner, her aunt Emilie Flöge, the widow of his brother Georg, Franziska Klimt, his sister Johanna Zimpel and his illegitimate son Gustav Ucicky all furnished Pirchan with stories about the artist and with illustrations from his estate. The only source among Klimt’s collectors, however, was Mäda Primavesi. All the artist’s other patrons had been left out on account of their Jewish background. Thus, today, the work provides a valuable, albeit incomplete collection of recollections from contemporary witnesses who have long since died.

The emphasis on the “Viennese” and “Austrian” aspects in this monograph was certainly intended as a nostalgic reminiscence of Vienna’s former role as Europe’s cultural capital. The modern painter Gustav Klimt was able to escape being branded a “degenerate artist,” as Pirchan presented him as a “typical Austrian” who had managed to elicit the “highest esteem for Viennese art.” Pirchan thus turned Klimt into a patriotic spearhead of Austrian culture, while deliberately excluding his Jewish promoters and commissioners. This was much in keeping with the National Socialists’ efforts to “revitalize Austria’s classical cultural tradition.” Pirchan’s populist style helped Klimt’s works gain great popularity. This revival of Klimt’s art resulted in a commemorative exhibition held by the regime in the midst of World War II in 1943. Emil Pirchan was invited to participate in this exhibition, which was meant to show Klimt as a “racially genuine Viennese.” In the monograph’s new edition, published in 1956, these nationalistic passages were toned down and rephrased.

Emil Pirchan, who continued to work as an artist, writer and professor until well into his old age, died on 20 December 1957 in Vienna. The year before his death, he had completed a publication about his teacher Otto Wagner. Already a year after his passing, a commemorative exhibition was held in his honor.

Literature and sources

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1956.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

- Beat Steffan (Hg.): Emil Pirchan. Ein Universalkünstler des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna 2018.

- Sophie Lillie: Die Gustav Klimt -Ausstellung von 1943, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 334-341.

- Eingehende Darstellung des Lebenslaufs. Emil Pirchan. www.donjuanarchiv.at/seemann/wallishausser/corpus/stary/lebenslauf.htm (08/29/2022).

- Iris Pawlitschko: Jüdische Buchhandlungen in Wien. „Arisierung“ und Liquidierung in den Jahren 1938 bis 1945, Dipl. Univ. Wien 1996. www.wienbibliothek.at/sites/default/files/files/buchforschung/pawlitschko-iris-j%C3%BCdische-buchhandlungen.pdf (08/29/2022).

- Emil Pirchan. emilpirchan.com (09/01/2022).