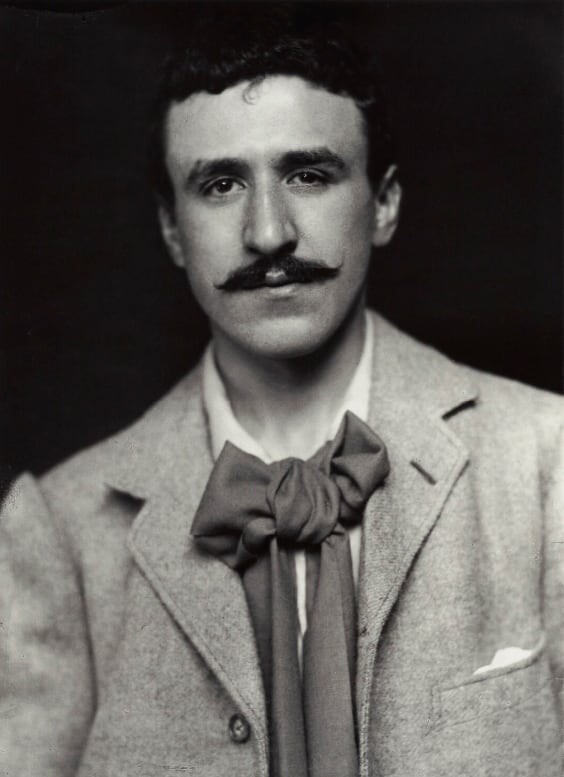

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh photographed by James Craig Annan, 1893

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The Scottish architect, designer, furniture designer, artisan, graphic artist and painter was influenced by the British Arts and Crafts movement, Symbolism and, like many of his contemporaries, Japonism. With his Gesamtkunstwerke he holds a prominent position in the European avant-garde of the fin de siècle.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (born MacIntosh) was born in Glasgow on 7 June 1868. He became an apprentice to the architect John Hutchinson in 1884 and worked as a draftsman for the architectural firm Honeyman & Keppie from 1888/89. In addition to his professional activities, Mackintosh attended evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art until 1894. It was there that he met James Herbert MacNair, Frances MacDonald and her sister Margaret MacDonald. Together they formed the artists’ group The Four, initially focusing on watercolors, posters and arts and crafts. MacNair and Frances MacDonald married in 1899, Mackintosh and Margaret MacDonald in 1900.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s early works included commissions of his employers John Honeyman and John Keppie, such as the interior decorations of the Glasgow Art Club and Craigie Hall (1892/93). He developed autonomous designs that were characterized by a functional approach, yet betrayed historic influences of Scottish architecture. He subsequently completed larger projects, such as the building of the Glasgow School of Art, which was constructed in two phases (1897–1899 and 1907–1909), as well as Queen's Cross Church (1896–1899). His most important achievements include a series of tearooms which he designed for the entrepreneur Catherine Cranston on Ingram Street (1900–1901) and Sauchiehall Street (1903) in the city center of Glasgow.

Like many of his contemporaries around 1900, Mackintosh perceived his role as an artist as that of an architect and designer responsible for the entire complex of a building, from the facade to the interior and the decoration. In keeping with the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art], he also designed furnishings, textiles, decorative elements and artistic objects. His simple, geometric designs for chairs with unusually high backs are still widely known today.

Mackintosh was prominently featured in various arts magazines and his work attracted the attention of Josef Hoffmann, then vice-president of the Secession, around 1900. Hoffmann asked his friend and client Fritz Waerndorfer – the art lover, entrepreneur and patron of the arts who would later co-found the Wiener Werkstätte spoke English fluently and was familiar with the latest British design trends – to travel to Glasgow and invite Mackintosh to participate in the “VIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Wiener Secession” [“8th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession”]. The exhibition was dedicated to arts and crafts and featured internationally renowned artists, including Charles Robert Ashbee and Henry van de Velde. The Mackintoshs and the MacNairs contributed an interior that was exhibited in room 10. Ludwig Hevesi reported:

“Upon entering this room your first thought will certainly be: ‘Toorop.’ And there is indeed a certain kinship. […] The room is white, the furniture is black, all wood is polished, thin, narrow, Secessionist ‘planks,’ with a few sudden squares of striking, colorful ornaments.”

The participation in this exhibition not only increased the popularity of Mackintosh, a corresponding member of the Secession: The works of the Scottish artists’ group The Four also had a lasting influence on the oeuvres of Joseph Maria Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann, Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and many designers of the Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903. Vienna’s Jugendstil was thus transformed into the reduced, geometric Secessionist style based on black-and-white contrasts.

The 1901 portfolio Haus eines Kunst-Freundes [House of an Art Lover] comprised 18 architectural designs by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and set the course for the further development of European architecture. Through art magazines and exhibitions, such as the “Prima Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Decorativa Moderna” [“First International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts”] held in Turin in 1902, Mackintosh’s art became known all over the world. In one of his most important works, Hill House in Helensburgh on the outskirts of Glasgow, built between 1902 and 1904, Mackintosh contrasted the rustic style of the rough plaster facade with the atmospheric design of the interiors in an ingenious combination of light, space, shape and decorative motifs.

According to Hevesi, the idea to decorate the music salon of Waerndorfer’s villa in Vienna’s Cottage-Viertel neighborhood was conceived as early as 1900, when the Mackintoshs had stayed there during the Secession Exhibition. When remodeling his villa, Waerndorfer commissioned the Mackintoshs, Kolo Moser and Hoffmann to redo the room in 1902. The three-panel frieze by Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh with the motif The Seven Princesses from the eponymous play by Maurice Maeterlinck was not installed until 1907, however.

In 1906, Waerndorfer traveled to London together with Gustav Klimt, Hoffmann and Carl Otto Czeschka to attend the presentation of Austrian arts and crafts at the “Imperial-Royal Austrian Exhibition” at Earl’s Court. They presumably met Mackintosh there on 5 May 1906, as is evidenced by Klimt’s announcement in a picture postcard sent to Emilie Flöge on the preceding day.

Mackintosh had become a partner at Honeyman & Keppie as early as 1901. In 1913, however, he resigned from the partnership and left Glasgow to move to England with his wife. After World War I, he received only few commissions. He concluded his career as an architect and turned to paintings, drawings and graphic works. He worked on a series of botanical studies in Suffolk in 1914–1915; he subsequently spent eight years in London during which he created several series of still lifes and progressive textile designs.

In the last few years of his life, he focused exclusively on painting: Between 1923 and 1927 he created some of his best watercolors in Southern France, inspired by the landscapes, villages and towns along the river valleys in the Pyrenees. Charles Rennie Mackintosh died of cancer on 10. December 1928. At the time of his death, he was living in London and had fallen into poverty.

Literature and sources

- Scottish Architects. Mackintosh. www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php (03/30/2020).

- Ludwig Hevesi: Aus der Sezession. Achte Ausstellung der „Vereinigung“, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 282-288.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Aus der Sezession, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 288-293.

- Georg Fuchs: Mackintosh und die Schule von Glasgow in Turin, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 10 (1902), S. 575-598.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 4. Jg., Heft 23 (1901).

- N. N.: Ein Mackintosh-Teehaus in Glasgow, in: Dekorative Kunst. Illustrierte Zeitschrift für angewandte Kunst, Band 13 (1905), S. 257-273.

- Fernando Agnoletti: The Hill-House Helensburgh. Erbaut von Architekt Charles Rennie Mackintosh, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 15 (1904/05), S. 337-361.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in London an Emilie Flöge in Wien (05/04/1906).

- Ludwig Hevesi: Haus Wärndorfer, in: Altkunst – Neukunst, Vienna 1909, S. 221–227.

- Elana Shapira: Modernism and Jewish Identity in Early Twentieth-Century Vienna: Fritz Waerndorfer and His House for an Art Lover, in: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Band 13 (2006), S. 52-92.