The Zuckerkandl Family

The Zuckerkandls were part of an elite of collectors among the Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna around 1900. Apart from East Asian art and Viennese Old Masters, the family members also collected works by Gustav Klimt. Furthermore, they supported the Wiener Werkstätte and the Secession as patrons.

The Jewish couple Leon and Eleonore Zuckerkandl came from Györ, Hungary, and had six children. Their oldest daughter Hermina died as early as 1894 and was not among Klimt’s collectors. Their second daughter Amalie, whose married name was Rudinger and later Redlich, as well as her brother Robert – who became professor of economics in Prague – were not known as ardent art collectors either. Hence it was the three brothers Emil, Victor and Otto as well as their wives who were responsible for the Zuckerkandls’ reputation as important patrons of the arts.

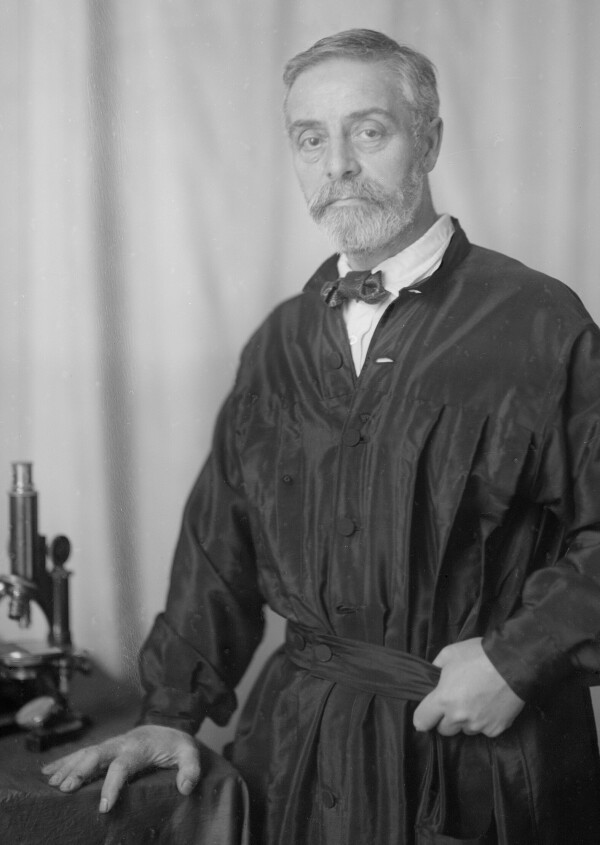

Emil Zuckerkandl photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1909

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Berta Zuckerkandl, photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1908

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Emil and Berta Zuckerkandl

Emil Zuckerkandl was the family’s oldest son. He was born in Raab on 1 September 1849. He studied medicine in Vienna and specialized in anatomy. Emil was appointed professor at the University of Vienna in 1888 and taught dissection. He married Berta Szeps, the open-minded, intellectual daughter of the writer Moriz Szeps, in 1886. Their only son Fritz was born in 1895. Together the Zuckerkandls hosted a salon for artists which was held at the couple’s apartments. Both spouses were greatly interested in art. While Emil had begun collecting East Asian art even before he met Berta, it is believed that he was introduced to modern art movements by his wife. Both supported rising young artists through their salon, including the Secessionists and, most prominently, their artist friend Gustav Klimt.

While Berta supported Gustav Klimt through her untiring reporting as a journalist, Emil Zuckerkandl invited the artist to watch him while he was dissecting. The sketches thus created formed the basis for the Faculty Painting Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and for Hope I (1903, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa). As a university professor, Emil Zuckerkandl also played an active part in the scandal surrounding the Faculty Paintings intended for the university’s Great Hall. While a group of professors opposed the installation of Klimt’s paintings, Emil supported his artist friend by signing a counterpetition, thus siding with Klimt in the dispute surrounding the Faculty Paintings.

Emil and Berta did not own any of Klimt’s oil paintings, but several of his graphic works, including Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans with 15 illustrations by Klimt as well as the drawing Standing Woman in a Frilled Dress (1904, Leopold Museum, Vienna), which allegedly shows Berta Zuckerkandl herself. It is unknown why Klimt did not create a painted portrait of his close friend and patron Berta Zuckerkandl.

In addition to Gustav Klimt, Emil and Berta also supported other modern artists. They for instance commissioned Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte to decorate their villa on Nußwaldgasse. Carl Moll, a frequent guest at the salon, captured the villa in several interior pictures.

Following Emil Zuckerkandl’s death on 18 May 1910, Berta continued to act as a patron of the arts. She commissioned the sculptor Anton Hanak to design a posthumous memorial of Emil Zuckerkandl for the courtyard of the University of Vienna, which the artist created between 1915 and 1923. As a writer, Berta continued to support modern art for the rest of her life.

She soon lacked the financial means to purchase large works of art, however. In 1916, she sold her husband’s collection of Asian art through the Dorotheum auction house. She fled the Nazi regime together with her son in 1938 and died in exile in Paris in 1945.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl, 1912, Verbleib unbekannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Auction of the Victor Zuckerkandl art collection at the Wawra Gallery, 1916, in: Kunsthandlung C. J. Wawra (Hg.): Kunstauktion von C. J. Wawra, Nummer 236, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1916.

© Heidelberg University Library

Victor and Paula Zuckerkandl

Victor was born on 11 April 1851 as the Zuckerkandls’ second-oldest son. He began a career as an industrialist. The successful entrepreneur, who rose to the well-paid position of director of the mining company Oberschlesische Eisenindustrie-Gesellschaft, had the financial means to invest part of his savings in works of art. Together with his wife Paula, née Freund, he compiled an extensive collection. Even though their collection focused on Viennese Old Masters such as Rudolf von Alt and Georg Ferdinand Waldmüller, it also included important works by Klimt. It is presumed that Victor was introduced to Gustav Klimt and the Secessionists by his sister-in-law Berta. Victor and Paula supported Klimt by commissioning portraits and purchasing paintings – especially through the Miethke Gallery.

The couple primarily owned landscapes by the modern artist. Victor for instance bought the painting Poppies in Bloom (1907, Belvedere, Vienna) in 1908. In 1911, he purchased Roses beneath Trees (around 1904, privately owned) as well as several drawings. The same year, he also commissioned Klimt to create a Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl (1912, current location unknown). From 1914 to 1916, Victor also owned Pallas Athene (1898, Wien Museum), which he had bought from the Klimt collector Fritz Waerndorfer. He later added the landscapes Avenue in Front of Kammer Castle on the Attersee (1912, Belvedere), Malcesine on Lake Garda (1913, current location unknown, missing since the end of World War II in 1945), Church in Cassone on Lake Garda (1913, privately owned) and Litzlberg am Attersee (around 1915, privately owned) to his collection.

When Victor Zuckerkandl bought the spa and treatment facility Sanatorium Purkersdorf in 1903, he commissioned Josef Hoffmann – presumably also on the recommendation of his sister-in-law Berta – to remodel it. Together with Kolo Moser, Hoffmann turned the building into a modern Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art], which housed a large part of the family’s Klimt collection. Meanwhile, Victor’s personal villa in Purkersdorf had been built in the Gründerzeit style and included a pavilion that housed his collection of Asian art. Victor’s nephew Fritz, the son of Berta and Emil, was a co-owner of the sanatorium.

In 1916, the steel magnate left Vienna and moved to Berlin with his family, selling most of his art collection on this occasion. In October, Victor sold more than 400 objects via the Kunsthaus C. J. Wawra auction house, including several drawings by Klimt as well as Pallas Athene, which went for 3.100 crowns (approx. 5.600 euros). He bestowed his collection of Asian art on the museum in Breslau. The remaining Klimt paintings were moved to Berlin, where they were hung in the stairwell of the new Villa Zuckerkandl in Grunewald. The Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl was presented in a prominent position in the living room above a chimney, in a paneled niche installed specifically for this purpose.

Villa Zuckerkandl in Berlin

After Victor and his wife passed away within months of each other in 1927, the estate was divided among their heirs. Since the couple did not have any children, most of the estate went to Victor’s siblings, nieces and nephews. Parts of the collection were sold at the C. J. Wawra auction house in Vienna in 1928. The auction did not include a single work by Klimt, however. Paula’s portrait was intended to go to the Austrian Gallery [now Belvedere, Vienna] as a bequest. Instead, it was lost in Berlin in the turmoil of World War II.

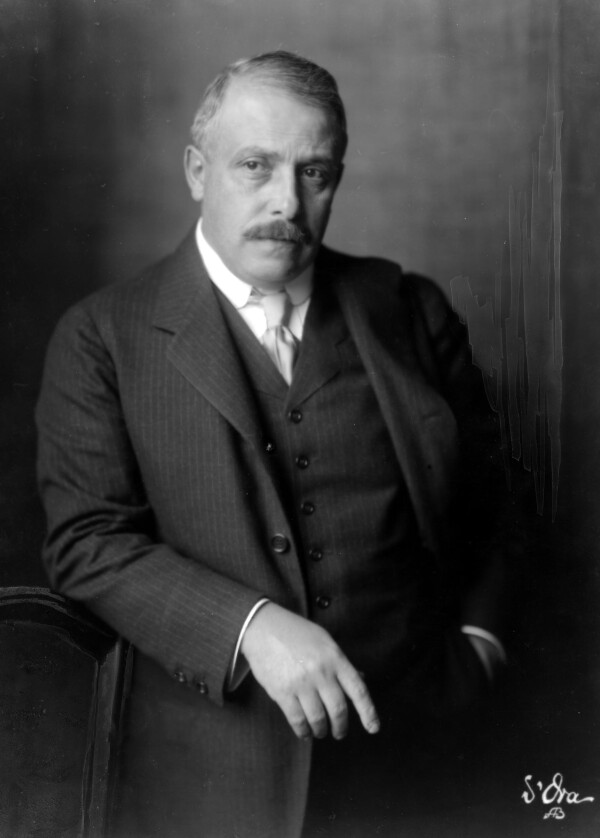

Otto Zuckerkandl photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1909

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, 1917/18, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Otto and Amalie Zuckerkandl

Otto was the youngest Zuckerkandl brother. He was born in Raab on 28 December 1861 and, like his oldest brother Emil, he pursued a career in medicine. After studying in Vienna he worked as an anatomist and later as a surgeon. In 1892, he was appointed a lecturer at the University of Vienna and eventually became a renowned urologist. He authored numerous reference books and scientific publications. In 1895, he married Amalie Schlesinger. The couple had a son, Viktor, and two daughters, Eleonore and Hermine.

Unlike other family members, Otto and Amalie did not have an extensive art collection of their own. Nevertheless, Otto followed his brothers’ example and actively supported modern art. He commissioned Josef Hoffmann to decorate his study at the family’s apartment in 1912 and Kolo Moser to design his ex libris. Around 1914, Otto commissioned Klimt, who had already portrayed his sister-in-law Paula, to paint a portrait of his wife Amalie. First drafts for the Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (1917/18, Belvedere) were created around that time. Since Amalie joined her husband in Lemberg, however, where she worked as a nurse during World War I, she was unable to pose for the artist. This caused a delay in the working process. The artist resumed work on the painting towards the end of the war in 1917. Klimt had received a total payment of 4000 crowns (approx. 7300 euros) for his initial work on the painting. The portrait was left unfinished, however, when Klimt died in 1918.

Amalie and Otto divorced the following year. Otto remarried only a month after their divorce. His second wife was the pianist Margarete Gelbard. Their marriage lasted only two years, until Otto’s unexpected death in 1921. It is presumed that Amalie sold her portrait after her divorce or after her former husband’s death to Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, who is documented as the work’s owner from 1928 at the latest. The work was restored to the family, however, and sold during the Nazi regime to the Neue Galerie in Vienna by Amalie’s youngest daughter Hermine, whose married name was Müller-Hofmann. It was eventually received by the Belvedere as a gift.

Amalie, who had converted to Judaism for her husband in 1895, was persecuted by the Nazi regime after Austria had become part of the German Reich with the “Anschluss” of 1938. Together with her daughter Eleonore (called “Nora,” whose married name since 1921 was Stiasny), she was deported to the Belzec extermination camp in 1942, where they were both murdered.

It is believed that Eleonore had received the painting Roses beneath Trees from the estate of Victor and Paula Zuckerkandl as a present from her brother Viktor jun. She sold it in 1938, with the intention of financing her escape from the regime. It was restored to her heirs following a restitution lawsuit in 2021/22.

Literature and sources

- Universität Wien. 650 plus- Geschichte der Wiener Universität.. Emil Zuckerkandl. geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/personen/emil-zuckerkandl-prof-dr (04/07/2020).

- Universität Wien. monuments. Emil Zuckerkandl. monuments.univie.ac.at/index.php (04/07/2020).

- Ö1. Das Porträt der Amalie Zuckerkandl. oe1.orf.at/artikel/641943/Das-Portraet-der-Amalie-Zuckerkandl (04/06/2020).

- Der Standard. Ein Abschied für immer (03.06.2011). www.derstandard.at/story/1304553584968/ein-abschied-fuer-immer (04/06/2020).

- Der Standard. Das Porträt einer Ermordeten: Amalie Zuckerkandl (31.03.2008). www.derstandard.at/story/2379120/153-das-portraet-einer-ermordeten-amalie-zuckerkandl (05/06/2020).

- De Gruyter. Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis. Band 42: Heft 1. Berta Zuckerkandl – Netzwerkerin der Wiener Moderne: Über die Sammlungen Emile Zuckerkandl an der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. www.degruyter.com/view/journals/bfup/42/1/article-p128.xml (04/06/2020).

- Monika Mayer: Nicht nur Klimt, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 251-265.

- Reinhard Federmann (Hg.): Berta Zuckerkandl: Österreich intim, Erinnerungen 1892- 1942, Vienna 2013.

- Vera Brantl: Die familiären, politischen und kulturellen Netzwerke Berta Zuckerkandls, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 234-243.

- Gegenpetition der Professoren der k. k. Universität Wien an das k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht in Wien (presumably late March 1900). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht Präsidium Akten 266, Zl. 1.126/1900 fol. 15, .

- Hermann Muthesius: Landhäuser. ausgeführte Bauten mit Grundrissen, Gartenplänen und Erläuterungen, 2. Auflage, Munich 1922.

- Versatz-, Verwahrungs- und Versteigerungsamt (Hg.): Nachlass Hofrat Professor Emil Zuckerkandl. Auserlesene Sammlung von Altwiener Porzellan. Hervorragende Alt-China- und Japan-Sammlung, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1916.

- Kunsthandlung C. J. Wawra (Hg.): Kunstauktion von C. J. Wawra, Nummer 236, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1916.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- N. N.: Professor Dr. Otto Zuckerkandl gestorben, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 03.07.1921, S. 5.

- Prager Tagblatt, 03.07.1921.

- Karteikarte Nr. 979 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf von »Rosen« (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 683 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf von »Blühender Mohn« (08/31/1908).

- Karteikarte Nr. 472 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 484 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 488 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 490 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 495 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 500 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (03/14/1911).

- Karteikarte Nr. 480 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf einer Zeichnung (12/19/1911).

- Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 34 (1914), S. 140.

- Franz Eder, Ruth Pleyer: Berta Zuckerkandls Salon – Adressen und Gäste, Versuch einer Verortung, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 212-233.