Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings

→

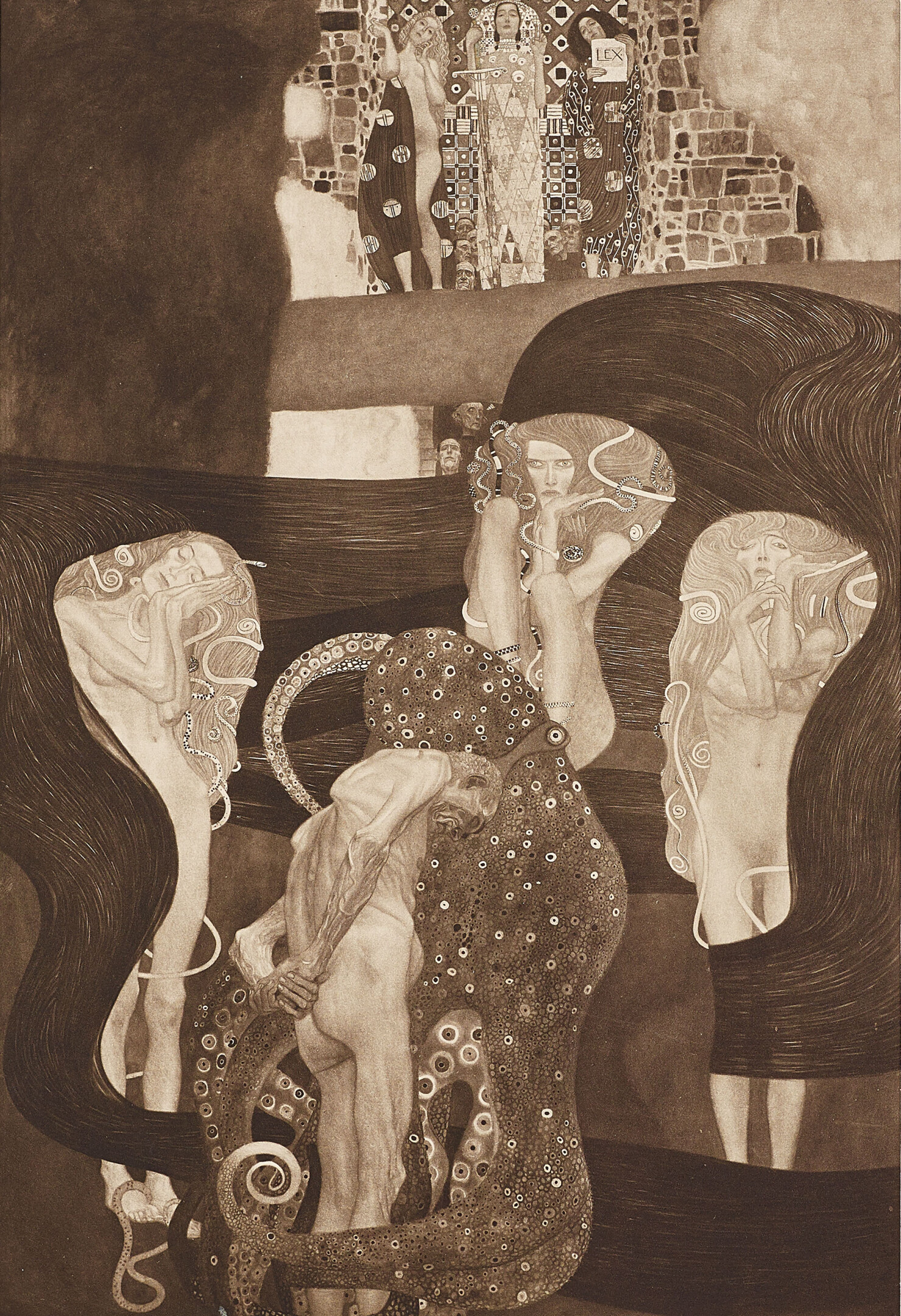

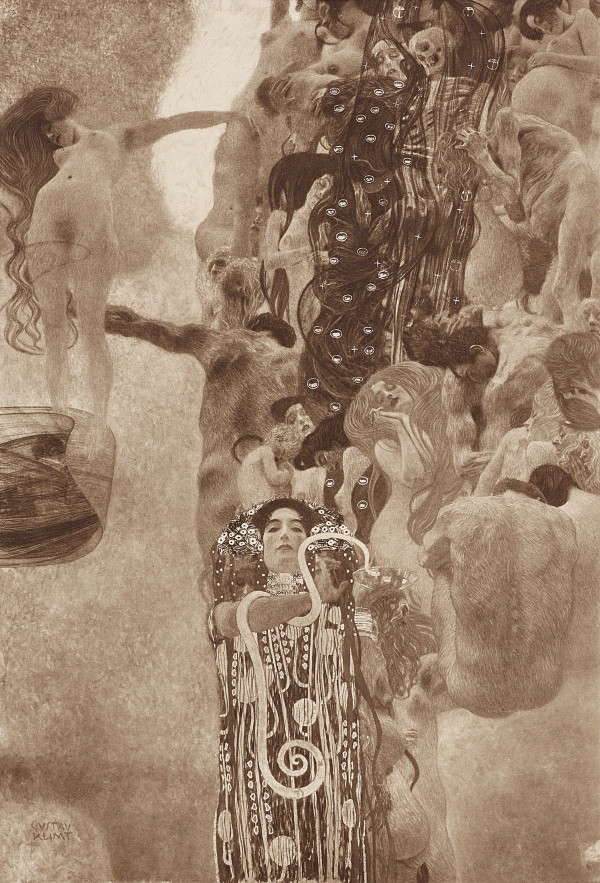

Gustav Klimt: Medicine, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Precious Portraits of Illustrious Ladies

From 1904 onward, Klimt carried the ornamentation introduced in the portrait of Emilie Flöge further in Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein and Portrait of Fritza Riedler. The background as a geometric and abstract foil for the naturalistically treated figure, as well as the use of gold and silver, became increasingly important, heralding characteristics of the Golden Period.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Colorful Floral Mosaics

Gustav Klimt also spent the summers from 1904 to 1907 in Litzlberg on the Attersee, where he found and painted profusely flowering meadows in the vicinity of his domicile, the Bräuhof. Employing a Pointillist style, he created allegorical and mysterious excerpts of nature based on his own experience.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Cottage Garden with Sunflowers, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Eros and Vanitas

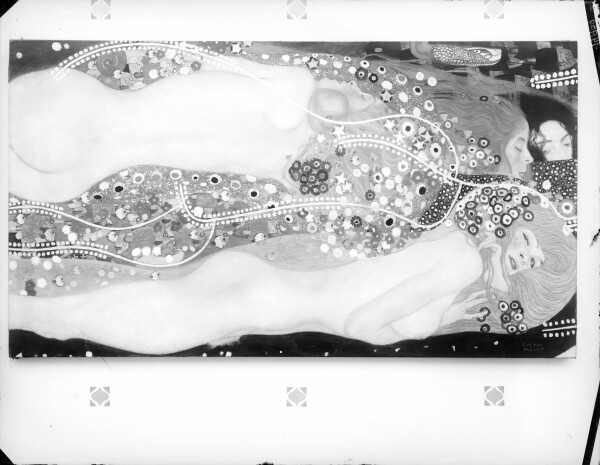

Between 1904 and 1906, Gustav Klimt held on to his allegorical, fairy-tale-style compositions of previous years with the motif of an erotically charged underwater world in Water Snakes I (Parchment) and Water Snakes II. He allegorized transience as central theme in the painting The Three Ages of Woman.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

© National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rome

Faculty Paintings. The Klimt Affair

With the Faculty Paintings of Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, Klimt not only developed into a radical protagonist of modernism, but also defined and defended his personal freedom as an artist in the face of ongoing criticism and rejection. In 1905 Klimt put an end to the affair surrounding the Faculty Paintings, as he resigned from the state commission and, with the help of the Lederers, paid back the fee he had received by then.

To the chapter

→

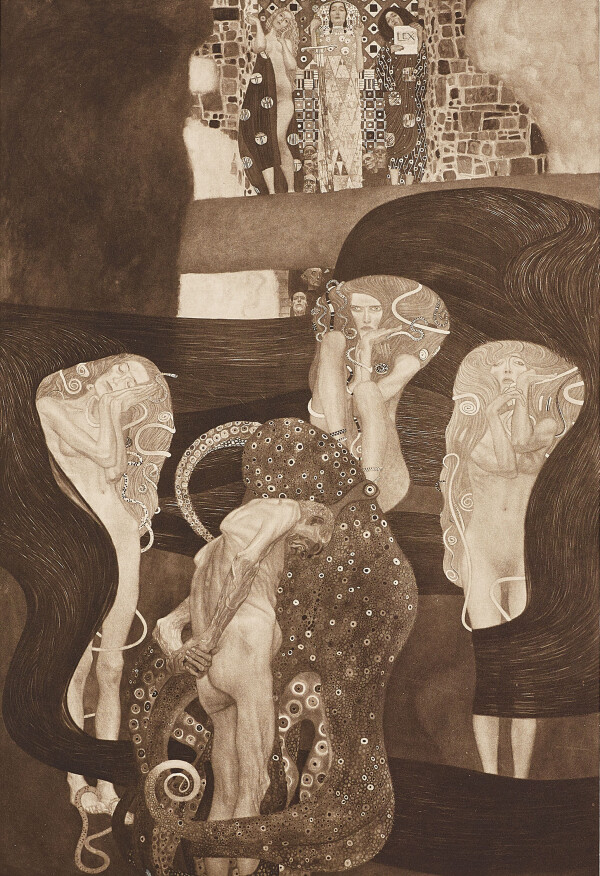

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence, 1903-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Exhibition Activity

In 1904, the Vienna Secession wished to present a number of paintings by Gustav Klimt at the St. Louis World’s Fair in the United States. After the Imperial-Royal Ministry for Culture and Education had declined the proposal, the association canceled its participation altogether. Instead, Klimt exhibited his works in Dresden, Munich, and Berlin in 1904/05.

To the chapter

→

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster of the second exhibition of the Deutscher Künstlerbund in Berlin, 1905, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Drawings

In 1903/04, Gustav Klimt switched to a hard, pointed pencil on Japan paper for his drawings. As he continued the theme of the underwater world, he turned to the erotic depiction of reclining women more and more. The studies for female portraits showcase frills and robes, while he prepared allegorical subject matter with naturalistic nude studies.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Two female nudes embracing, 1903-1907, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Precious Portraits of Illustrious Ladies

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

© bpk | Bavarian State Painting Collections

Moriz Nähr: Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

From 1904 onward, Klimt carried the ornamentation introduced in the portrait of Emilie Flöge further in Portrait of Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein and Portrait of Fritza Riedler. The background as a geometric and abstract foil for the naturalistically treated figure, as well as the use of gold and silver, became increasingly important, heralding characteristics of the Golden Period.

Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein

Around 1900, the Wittgenstein family was one of the richest families in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Karl Wittgenstein made his fortune in the iron and steel industry and was an important collector of modern art, as well as a patron of the Vienna Secession and of the Wiener Werkstätte.

It was presumably in early 1904 that Karl Wittgenstein and his wife Leopoldine commissioned from Gustav Klimt a portrait of their daughter Margarethe. Klimt wrote in a letter to her mother:

“It is with the greatest pleasure that I am prepared to take on your assignment, if a small postponement is possible. I won’t be able to do much before mid-March.”

As usual, Klimt prepared the portrait with several sketches, in which he was mainly concerned with the sitter’s pose and details of the clothing. It seems that the artist devoted himself intensively to the execution of Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) until early 1905, when Klimt approached Karl Wittgenstein with a loan request:

“[...] may I ask you for your picture of ‘The Golden Knight’ for the Berliner Kunstausstellung? And also for the portrait of your daughter, although the picture is not yet finished? – The exhibition will probably last until November. – I have to fill a room there and would need both pictures most urgently.”

The still unfinished painting was thus exhibited in Berlin at the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”] in May 1905. On 7 January that same year, Margarethe Wittgenstein married the American industrialist Jerome Stonborough and subsequently occasionally anglicized her name to Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein. The couple moved to Berlin, where the sitter attracted a lot of attention through her personal presence at the exhibition, as could be read in the Neue Freie Presse. The state of the painting at the time was documented photographically and reproduced in the magazine Kunst und Künstler.

As to his female portraits, Klimt entered a new stylistic phase, which he had prepared with Portrait of Emilie Flöge (1902/03, Wien Museum) through the ornamentation of the dress, and which he now continued in the geometrically abstract design of the background. In doing so, he reformulated a principle of Viennese Modernism: the contrast of strict geometry with painterly brilliance and a naturalistic depiction of figures. Thus he also depicted Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein in a delicate white dress and stole, the materiality of which suggests velvet jacquard. While the figure – especially the area of the face and hands – is rendered in a highly naturalistic manner, Klimt structured the background in zones of color. While the exhibition was still on, Gustav Klimt announced in a letter to Karl Wittgenstein that he wanted to improve the portrait by completing the work:

“[…] not because the picture is not ready yet – but first and foremost because it is still not good enough […]. I hope to be able to finish the picture after the exhibition is over in fall, and I also hope that it will finally come out a good portrait.”

Compared to the state in the photograph, Klimt especially modified the background. In the lower third of the picture, he introduced a black line with checkerboard pattern accents to separate the colored areas and added ornamental patterns in the field behind the head. In addition, he placed his signature and the date 1905 at the lower left of the painting, within the square signet in gold he had used several times by then for his female portraits.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Insight into the anniversary exhibition in Mannheim, May 1907 - October 1907

© Heidelberg University Library

Fritza Riedler

In the wake of Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, Klimt intensified the contrasting combination of the geometrization of space with the naturalistic depiction of the sitter Friederika “Fritza” Riedler. She was the wife of Dr. Aloys Riedler, a mechanical engineer from Graz who taught at the Technical University in Munich and was later called to Aachen and Berlin.

Klimt prepared Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna) with studies starting in 1904/05, experimenting with different sitting and standing positions as well as pieces of garment. For the executed painting he opted for an almost square format and depicted the sitter seated in an upholstered armchair. She wears a white dress, the ruffles, flounces, and bows of which Klimt depicted in a highly tactile manner, and jewelry in the form of a multistranded choker and a pearl necklace. The flatness of the background is only broken by the implied triangular composition of the sitter on the seating furniture to suggest an illusion of depth. Klimt reduced the presence of the armchair through the ornamentation of the fabric so that the surrounding areas practically dissolve. In this context, the wavy and almond-shaped pattern of the fabric was often interpreted in literature as the Eye of Horus, borrowed from divine Egyptian symbolism.

What is also particularly eye-catching is the mosaic-like backdrop around Fritza Riedler’s head, which brings to mind a stained glass window. According to Ludwig Hevesi, the surface had the effect of a “halo” or the “sweeping hairstyles of Velázquez’s infantas.” Klimt may indeed have been inspired by a portrait of Infanta Maria Teresa (1652/53, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) by the Spanish court painter Diego Velázquez, whose work he had dealt with during his student days. Klimt traveled to London in the spring of 1906, close to the time when he painted Portrait of Fritza Riedler, where, according to Erich Lederer, he also studied the works by Velázquez. According to Lederer, Klimt once even compared himself to the painter of the “Siglo de Oro,” the Spanish Golden Age: “There are only two painters: Velázquez and me!” Another important impulse for Klimt’s work was his journey to Italy, which took him to Venice and Ravenna in 1903. The Byzantine art he saw there and “the shimmering golden mosaics” had a lasting influence on his work.

A different state of Portrait of Fritza Riedler was published in 1918 in the first edition of the portfolio Das Werk von Gustav Klimt by art publisher Hugo Heller. The reproduction is still missing the small square with the artist’s signature and the date 1906, which Klimt inserted in the golden field near the left margin of the picture. In the finished work, he only modified a few details, including the squares of the wall surface and the ornamentation of the “halo.” Klimt presumably added these things for the presentation of the work at or after the “Jubiläums-Ausstellung Mannheim 1907” [“1907 Mannheim Jubilee Exhibition”], which took place at the Mannheim Kunsthalle in 1907. Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York), which is considered a key work of the Golden Period and in which the play of contrasts between gold-ornamented areas and naturalistic corporeality culminated, was also on view there.

Literature and sources

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969, S. 507, Nr. 10.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Thomas Zaunschirm: Gustav Klimt. Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein. Ein österreichisches Schicksal, Frankfurt am Main 1987.

- Johannes Dobai: Das Bildnis Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein von Gustav Klimt, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 5. Jg., Heft 8 (1960), S. 8-11.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Karl Wittgenstein [?], DLSTPW7 (vermutlich Mitte 1905), .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Leopoldine Wittgenstein [?], DLSTPW8 (vermutlich 1904), .

- Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 3. Jg. (1905).

- N. N.: Eröffnung der Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes. Telegramme der "Neuen freien Presse", in: Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 20.05.1905, S. 9.

- Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918, Tafel 7.

- Elisabeth Kamenicek: Die Wittgensteins als Sammler, Bauherren und Mäzene, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 123-147.

Colorful Floral Mosaics

Gustav Klimt: Roses beneath Trees, circa 1904, private collection

© bpk | RMN - Grand Palais

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Orchard (A Summer's Day), 1902/03, Carnegie Museum of Art, Patrons Art Fund

© Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Gustav Klimt: Cottage Garden with Sunflowers, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt also spent the summers from 1904 to 1907 in Litzlberg on the Attersee, where he found and painted profusely flowering meadows in the vicinity of his domicile, the Bräuhof. Employing a Pointillist style, he created allegorical and mysterious excerpts of nature based on his own experience.

In his landscapes, Klimt processed his visual impressions and created equivalents in color and form on canvas while focusing on his personal experience of nature. Not only does this group of paintings betray the influence of works of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism that had been on view at the epochal “XVI. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“16th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] at the beginning of 1903, but they also and above all reflect his own understanding of nature as a restful and inspiring retreat.

In Klimt’s lush orchards featuring flowering meadows or rose bushes in square format, the allegorical essence of the image of nature is specifically expressed in vibrant Pointillist dabs of color. In the painting Roses Beneath Trees (c. 1904, private collection), the painter placed three small rose bushes in the foreground as a contrast to the mighty treetops of three apple trees in the background, which are rendered as self-contained forms, whether spherical or oval, with short, slender trunks. What results is an expanse vibrating with an infinite variety of hues. Priority is given to the flickering coloristic effect, at the expense of spatial illusionism; only in the upper right corner does Klimt adumbrate a small piece of a cloudy sky and a hill.

There is a composition sketch for Roses Beneath Trees on page 55 of the sketchbook formerly owned by Sonja Knips. Since the painter used this booklet between 1897 and 1905, the painting can be assumed to have been created before or around 1904/05. It was exhibited for the first time in 1908 at the “Kunstschau Wien.” There is a poetic description of the roses by Berta Zuckerkandl, Klimt’s untiring apologist:

“And so the roses beneath the apple tree, which bends under its rich crop, give off a sweet, heavily intoxicating fragrance. Not bearing a single bud, these bushes are in full blossom, dreaming all the ecstasies of a summery delirium.”

In landscape depictions dating from a few years earlier, such as Orchard (A Summer’s Day) (1902/03, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) or his forest views, Klimt, employing a deliberately fragmented brushwork, had likewise encouraged the viewer’s gaze to wander across the canvas and discover the grandeur of nature.

In 1906 he devoted himself to the floral splendor of flowers and colors once again in Cottage Garden with Sunflowers (1906, Belvedere, Vienna). Markus Fellinger discovered a newspaper article in Die Zeit from 25 December 1906 in which a cottage garden dotted with sunflowers is described as a new work by the “prince of painters”:

“The third work is a peasant garden: superbly stylized, almost conceived as an idealized carpet and yet of the greatest charm of harmonious color effects achieved by the combination of ordinary flowers—sunflowers, auriculas, etc.”

As the Pointillist flickering abates, the sunflowers, with their attention to detail, dominate this floral mosaic sprinkled with phlox, carnations, and zinnias, among others. They would find their continuation in the years to come during a succession of stays on the Attersee.

Literature and sources

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975, S. 338.

- Stephan Koja: Tafeln, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 282.

- Stephan Koja: Frisch weht der Wind der Heimat zu… Neue Beobachtungen zur Topografie von Klimts Landschaftsbildern, in: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere (Hg.): Belvedere. Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst (2007), S. 192-221.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2015.

Eros and Vanitas

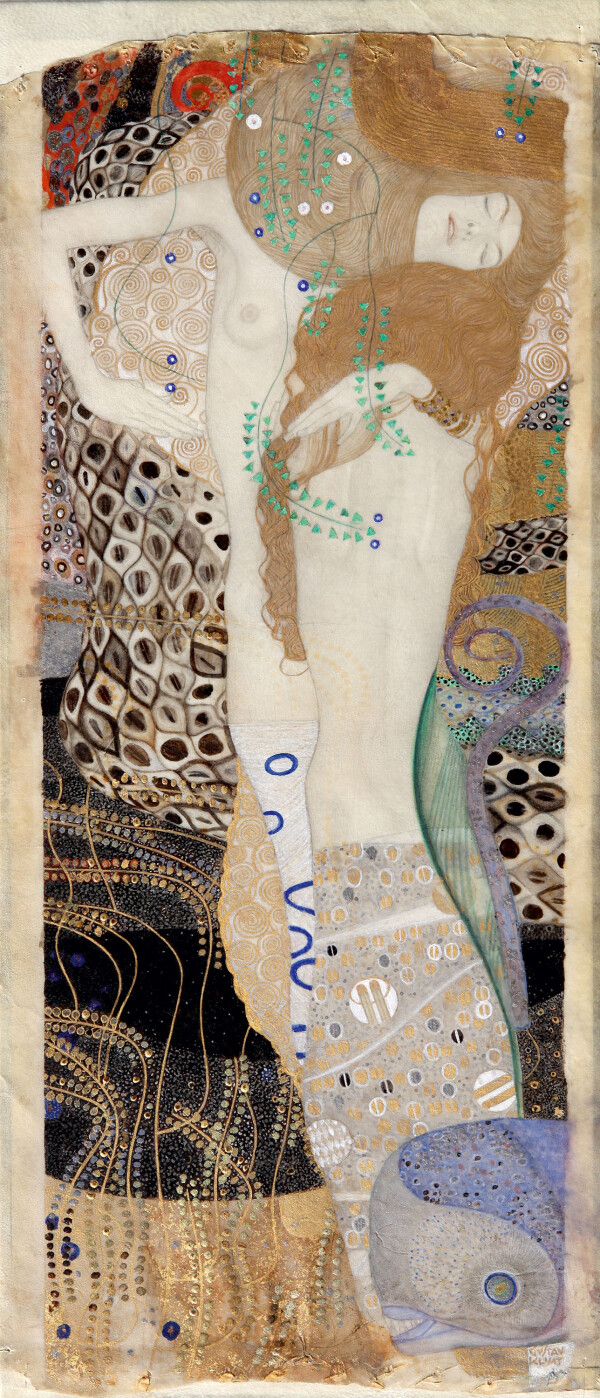

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes I (Parchment), 1904, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

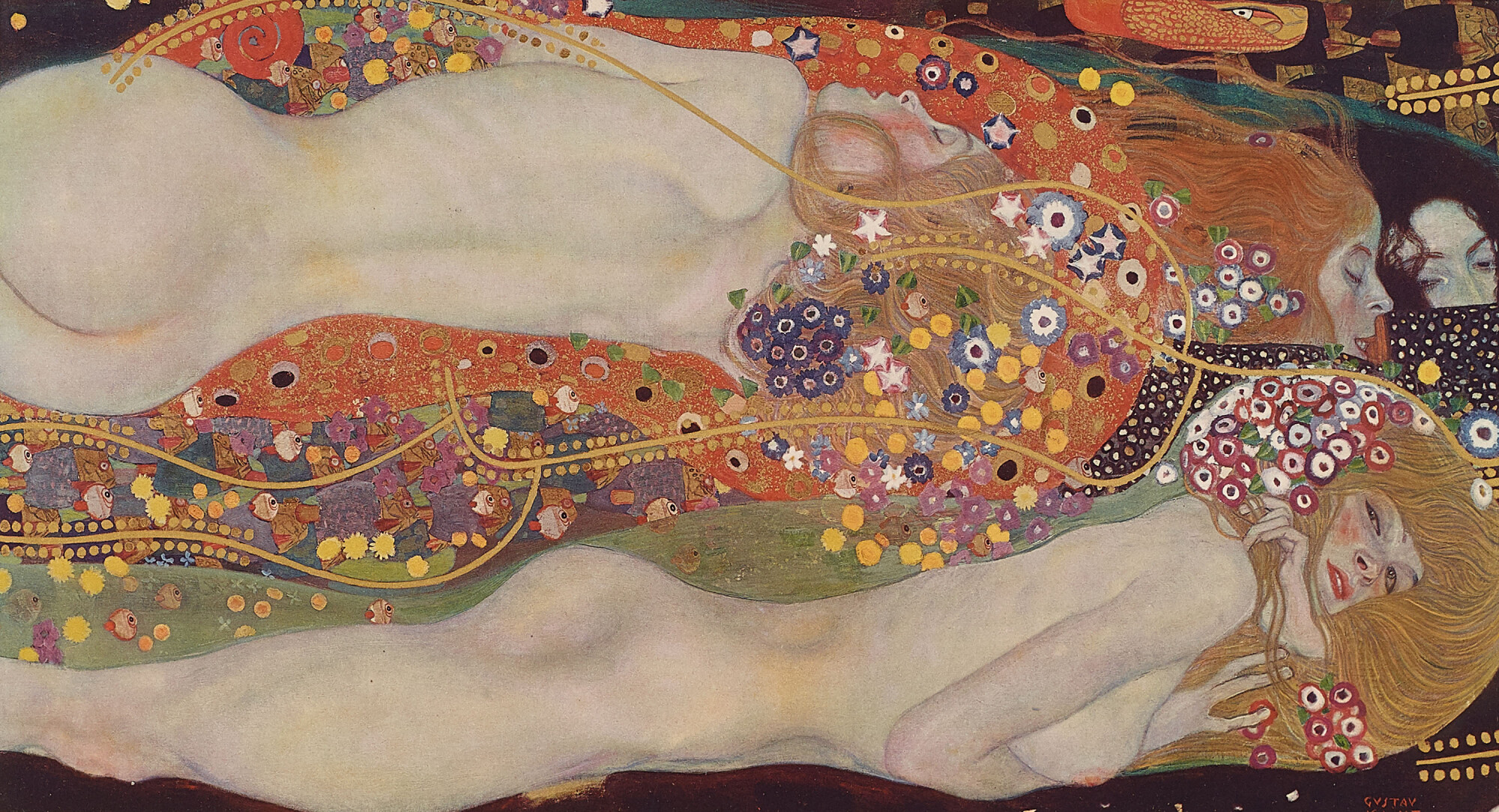

Between 1904 and 1906, Gustav Klimt held on to his allegorical, fairy-tale-style compositions of previous years with the motif of an erotically charged underwater world in Water Snakes I (Parchment) and Water Snakes II. He allegorized transience as central theme in the painting The Three Ages of Woman.

Gustav Klimt first dealt with fairy-tale-like, mythical water creatures in Moving Water (1898, private collection) and then continued the theme in the paintings Water Nymphs (Silverfish) (1902/03, Albertina, Vienna), Goldfish (1901/02, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Dübi-Müller-Stiftung), Will-o’-the-Wisp (1903, private collection), and Daphne (1902/03, private collection). In Water Snakes I (Parchment) (1904, reworked before 1907, Belvedere, Vienna) and Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection), he revisited the sensual and erotic water creatures, mermaids, and fishes reminiscent of works by the Symbolists Fernand Khnopff and Jan Toroop.

Water Snakes I (Parchment)

Starting in 1903, Klimt made numerous preparatory studies and drawings in the context of the “Water Snakes.” Concentrating primarily on the depiction of lesbian couples, Klimt produced a compositional sketch for Water Snakes I (1904, private collection, S 1982: 1355). He executed the work, which might have been done in preparation for Water Snakes II, in mixed media on a small sheet of parchment (50 x 20 cm), using pencil, watercolor, and body color, as well as silver and gold bronze and applications in gold. The materiality was commented upon in an article about Gustav Klimt’s new works (“Neue Arbeiten von Gustav Klimt”) in Die Zeit, which appeared in 1906:

“[…] What is probably the most beautiful one, the fourth, shows an embracing female couple with golden hair and fine, delicate bodies; […] it is painted on parchment; a material that lends an outrageously gauzy and delicate expression to the artist’s most recent and finest intentions. Here, too, the ground is purely decorative: snake skins, stylized sea animals, gold and silver ornaments in rich, hieratic splendor.”

In addition to the painting style, the erotic and sensual content of the depiction of dreamy, naked young women embracing intimately is particularly characteristic of Klimt. The two nude figures are surrounded by maritime creatures and abstracted plants in an ornamentally dissolved underwater world. The artist continued to modify the work until 1907 – changes that were documented in their intermediate states in two black-and-white photographs. The first presentation of Water Snakes I took place in the “Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Exhibition”] at Galerie Miethke in July 1907.

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes II, 1904, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Moriz Nähr: Water snakes II, June 1908 - November 1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XX. Secession exhibition, April 1904 - June 1904, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Water Snakes II

Compared to Water Snakes I (Parchment), in Water Snakes II Klimt tilted the nudes floating in the water into a larger landscape format (80 x 145 cm). At the “XX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“20th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], the painting was still unfinished, according to newspaper reports. The work was not added until four days after the opening on 29 March 1904. A photograph by Moriz Nähr allows a glimpse into Exhibition Room VI, showing Water Snakes II installed in its first, unfinished state and documented as such. Klimt would still make changes and additions to it until 1908. The journalist Armin Friedmann visited the exhibition, which he reviewed in the Wiener Abendpost, describing in detail the painting presented there for the first time:

“Klimt has painted a new picture, which he calls Water Snakes. Again it is the secret and wondrous confession of a cossetted dweller in a world of dreams. With infinite delicacy, a timid underwater green announces itself, a bluish gray trembles away, a somewhat warmer brown heralds itself, while gold and a deep, dark blue lead over into the decorative. We are gently rocked between reality, dream, and ornament. The female bodies iridesce as they play on the bottom of the sea. Two overly slender little mermaids à la Jan Toorop frolic on its colorful pebbles with fabulous water snakes in a sinful yet innocent game.”

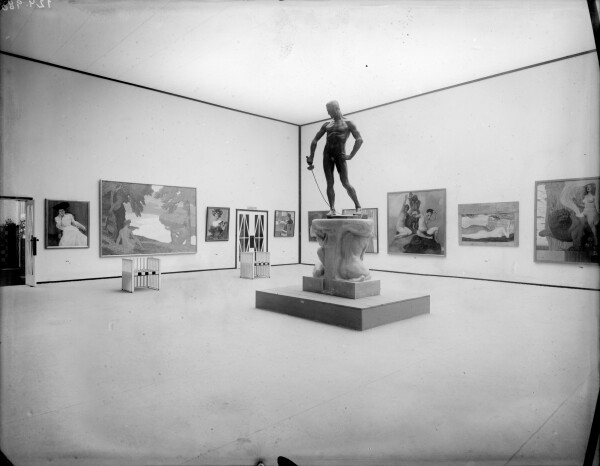

At the turn of the year 1904/05, Klimt presented his work a second time, this time in the “Ausstellung der Wiener Kunstvereinigung Secession” [“Exhibition of the Association of Artists Secession in Vienna”] at the Volksgartensalon in Linz. This was followed in May 1905 by the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”] in the rooms of the Berlin Secession. Klimt was given his own room, where he was to show 13 paintings. The room was to stand out from the rest of the exhibition as a kind of “Collective Klimt Show,” but the elaborate decoration work planned for this purpose led to delays. Furthermore, there were customs problems with the delivery of the paintings, which is why Klimt’s room was only made accessible to the public two weeks after the opening of the exhibition on 19 May 1905.

Gustav Klimt: The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

© National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rome

The Three Ages of Woman

Klimt’s major allegorical work from this period – The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) – was prepared by the painter between 1904 and 1905 with sensitive studies of the individual figures, mother-and-child studies, and a transfer sketch (1904, private collection). The executed work shows the three ages personified by female figures: an old woman viewed in profile, covering her face with her hair and one of her hands, and next to her a young woman affectionately holding a child in her arms. With this composition, Klimt defied both common spatial and perspectival constructions and narrative techniques. Instead, in his symbolic interpretation of transience, he placed three figures in front of an abstract, ornamentally structured background. With the juxtaposition of old age, youth, and childhood, Klimt drew upon the tradition of vanitas personifications, which in The Three Ages of Woman, however, he depicted with their eyes closed and introverted.

The work was first presented in May 1905 as part of the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”] in Berlin together with Water Snakes II and Portrait of Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich). According to the Neue Freie Presse, critics “acknowledged the artful execution,” but the response of visitors to The Three Ages of Woman was also described as follows:

“His oddities may have caused some headshaking, which especially holds true for the picture entitled ‘The Three Ages,’ which is installed on the main wall as if with provocative intention. One can see three nude figures, a child, a young woman, and an old crone, and it is above all the latter’s withered and devastated body that is depicted with repulsive realism. [...] The whole scene is surrounded by many a peculiar play of colors.”

Literature and sources

- Colin B. Bailey (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Modernism in the Making, Ausst.-Kat., National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), 15.06.2001–16.09.2001, Ottawa 2001.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger: Die Ursucht oder die Lust am eigenen Körper. Feminine Sexualität im Werk von Gustav Klimt, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jane Kallir, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 22.10.2015–28.02.2016, Munich 2015, S. 30-47.

- Armin Friedmann: Sezessions=Ausstellung, in: Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 08.04.1904, S. 1-3.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012, S. 166-181.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Berlin an Emilie Flöge in Wien (05/19/1905).

- N. N.: Eröffnung der Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes. Telegramme der "Neuen freien Presse", in: Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 20.05.1905, S. 9.

Faculty Paintings. The Klimt Affair

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XVIII Secession Exhibition, November 1903 - January 1904, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Medicine, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence, 1903-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Josef Hoffmann: Room design for the Association at the World's Fair in St. Louis, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

With the Faculty Paintings of Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, Klimt not only developed into a radical protagonist of modernism, but also defined and defended his personal freedom as an artist in the face of ongoing criticism and rejection. In 1905 Klimt put an end to the affair surrounding the Faculty Paintings, as he resigned from the state commission and, with the help of the Lederers, paid back the fee he had received by then.

The genesis of Klimt’s Faculty Paintings for the auditorium of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna began with their commission in 1894 and extended over many years, with numerous preliminary studies, alterations, and additions, until their completion around 1907. The artist’s transformation from Historicist decorator to internationally recognized Symbolist manifested itself in this work. Klimt thus increasingly detached himself from the design sketches approved in 1898 while also distancing himself from the client’s understanding of art and morals. The paintings caused veritable scandals when they were first presented.

The first work to be shown publicly was Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), which was on view at the “VII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“7th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] in March 1900. Criticism culminated in a petition launched by university professors opposing the display of Klimt’s Faculty Paintings. The main points of criticism were the choice of motifs, which deviated from traditional iconography, the inappropriate composition, and the incomprehensible language of form and imagery. Klimt had depicted Philosophy as coming into being, fruitful existence, passing away, mystery of the world, and knowledge. His sources of inspiration for the Symbolist painting appear to have derived from Richard Wagner’s Der Ring der Nibelungen [The Ring of the Nibelung], as well as theosophical thought.

Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) followed in 1901, when it was presented for the first time at the “X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“10th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], featuring the figure of Hygieia and a procession of suffering humans embodying disease, pain, and death. Klimt thus continued the “stream of humanity” begun in Philosophy.

This time, more than 20 members of parliament approached the Imperial-Royal Minister for Culture and Education with an interpellation criticizing the progressive painting. Furthermore, the sixth issue of Ver Sacrum was confiscated because the images of a naked pregnant woman it contained – nude studies and a reproduction of Medicine – violated public morality.

Jurisprudence (1903–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) represents the culmination of the Faculty Paintings. It was shown for the first time together with Medicine and Philosophy in November 1903, at the “XVIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession Wien. Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“18th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession – Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”]. Klimt had taken Symbolism even further in an even more progressive way by having Truth, Justice, and Law prevail over a condemned man in the grip of three furies and a kraken.

Once again, Klimt’s works provoked numerous critical statements, satirical caricatures, and ridicule, with the relentless depiction of nudity and ugliness in particular being considered perverse and shocking. Karl Kraus was on the side of the critics; among the supporters, on the other hand, were the Secessionists and such prominent personalities as Hermann Bahr, Ludwig Hevesi, and Berta Zuckerkandl. Together with Matsch’s contributions to the auditorium of the university, Klimt’s Faculty Paintings now finally longer complied stylistically with the overall concept.

In 1904, the Secession wanted to present Klimt’s Philosophy and Jurisprudence, among others, at the St. Louis World’s Fair in the United States. However, the ministry rejected the plan on the grounds that not enough members of the Secession would have been included to adequately represent the association. This was probably only to prevent the exhibition of the controversial Faculty Paintings. The Secession completely canceled its participation in the St. Louis World’s Fair and shortly thereafter published a special issue of Ver Sacrum entitled Die Wiener Secession und die Ausstellung in St. Louis [“The Vienna Secession and the Exhibition in St. Louis”]. The issue also included the official reply to the ministry:

“In our opinion, the value of an art exhibition is not determined by the number of objects, but by their quality and the way they are displayed. [...] Our association regrets that its artistic view has not found recognition at the honorable Imperial-Royal Ministry of Education [...].”

In 1905 the installation of the paintings on a trial basis at their destination at the university was rejected, while the works by Matsch were approved for reasons of economy. Klimt then wanted to resign from the commission as a whole and waive his fee. In a letter, he explained his motives and criticized the way of art promotion practiced by the state and its interference with artistic freedom:

“Enough of censorship. I will resort to self-help. I want to get away. I want to return to freedom from all this unedifying ridiculousness that impedes my work. I refuse all support from the state, I will do without all of it.”

In May 1905, with the help of the Viennese industrialists and collectors August and Serena Lederer, Klimt finally bought back the Faculty Paintings and returned all the fees he had received by then, amounting to 30,000 crowns (ca. 237.101,70 Euros), to the ministry. Matsch’s central picture and the spandrels were installed in the great hall, and the remaining fields remained empty.

Following the scandal of 1905 surrounding the Faculty Paintings, which was widely covered in the press, Gustav Klimt noticeably withdrew from the public eye. He also resigned from the Secession together with the so-called “Klimt Group.” It was probably not only because of his artistic reorientation but also due to his personal withdrawal that Klimt exhibited only once in 1906. The exhibition “Old and Modern Pictures. Tableaux anciens et modernes. Ausstellung von Werken alter und moderner Meister” took place at Galerie H. O. Miethke from January to March 1906. Here the controversial Faculty Painting of Jurisprudence was presented to a Viennese audience again for the first time since the “Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition.”

The final versions of Klimt’s Faculty Paintings were shown together again in 1907 at Galerie Miethke and at Galerie Keller & Reiner in Berlin. In Berlin in particular, the revised works elicited a positive response throughout and helped Klimt to further exhibitions in Germany at Galerie Arnold and Kunsthandlung Paul Cassirer. The once scandalous works were destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria in 1945.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks | 1889 – 1894 (Decorator of the Ringstraße)Faculty Paintings. Awarding of the Commission

-

Klimt's Artworks | 1895 – 1897 (Symbolism in Klimt’s Oeuvre)Faculty Paintings. First Sketches

-

Klimt's Artworks | 1898 – 1900 (Cradle of Modernism)Faculty Paintings. Philosophy

-

Klimt's Artworks | 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

Literature and sources

- Markus Fellinger, Michaela Seiser, Alfred Weidinger, Eva Winkler: Gustav Klimt im Belvedere. Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012, S. 31-281.

- Peter Weinhäupl: Baustelle Fakultätsbilder. Klimts streitbare Moderne, die ungewollte Anerkennung und der Untergang, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 49-76.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903), S. 5.

- N. N.: Die „Philosophie“ von Klimt und der Protest der Professoren, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 3. Jg., Heft 10 (1900), S. 151-166.

- N. N.: Die Secession und die Weltausstellung in St. Louis, in: Neue Freie Presse, 04.02.1904, S. 6.

- Galerie H. O. Miethke (Hg.): Old and modern pictures. Tableaux anciens et modernes, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 00.07.1906–00.00.1906, Vienna 1906.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Christian M. Nebehay: Skandale um die Fakultätsbilder, 1900-1905, in: Gustav Klimt. Sein Leben nach zeitgenössischen Berichten und Quellen, Vienna 1969, S. 144-177.

- Gustav Klimt und der Staatsauftrag Archivalien des Monats. Österreichisches Staatsarchiv. geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/biblio/gustav-klimt-und-der-staatsauftrag (09/19/2022).

- Die Fakultätsbilder von Gustav Klimt im Festsaal der Universität Wien. Universität Wien. geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/artikel/die-fakultaetsbilder-von-gustav-klimt-im-festsaal-der-universitaet-wien (09/19/2022).

- Berta Zuckerkandl: Gustav Klimt's Decken-Gemälde, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 22 (1908), S. 68-73.

- Horst-Herbert Kossatz: Der Austritt der Klimt-Gruppe. Eine Pressenachschau, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 20. Jg., Heft 141 (1975), S. 23-26.

Exhibition Activity

Josef Hoffmann: Room design for the Association at the World's Fair in St. Louis, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

In 1904, the Vienna Secession wished to present a number of paintings by Gustav Klimt at the St. Louis World’s Fair in the United States. After the Imperial-Royal Ministry for Culture and Education had declined the proposal, the association canceled its participation altogether. Instead, Klimt exhibited his works in Dresden, Munich, and Berlin in 1904/05.

In 1904, the Vienna Secession was to participate in the St. Louis World’s Fair. Six works by Gustav Klimt and several sculptures by Franz Metzner and Ferdinand Andri were to be presented in an exhibition room made available to the association. The interior design of the room was to be conceived by Josef Hoffmann. Unfortunately, the Ministry of Culture and Education rejected the plan. The reason given by the ministry was that not enough members of the Secession would have been featured at the World’s Fair to adequately represent their association. What is more likely is that the presentation of the controversial Faculty Paintings of Jurisprudence (1903–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) should be prevented.

In response to this rejection, the Secession completely resigned from its participation in the St. Louis World’s Fair. Shortly afterwards, the association published a special issue of Ver Sacrum entitled The Vienna Secession and the Exhibition in St. Louis. It also contained the ministry’s official reply. The Secession commented the ministry’s rejection as follows:

Josef Groller: Poster of the Great Art Exhibition Dresden, 1904, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Leopold Stolba: Poster of the XX Secession Exhibition, 1904, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G)

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

“In our eyes, the value of an art exhibition is not determined by the number of objects, but by their quality and by the way they are arranged. […] The association regrets that its artistic point of view has not been recognized by the honorable Imperial-Royal Ministry of Education […].”

Aside from the written statement, the special issue also contained reproductions of the works by Klimt and the other artists who were supposed to be on display at the World’s Fair, as well as the interior designs by Josef Hoffmann.

Exhibitions in Germany

Instead, Gustav Klimt took part in the “Große Kunstausstellung Dresden” [“Great Dresden Art Exhibition”] and the “X. Ausstellung der Münchner Secession: Der Deutsche Künstlerbund” [“10th Exhibition of the Munich Secession: The Union of German Artists”] in 1904. In Dresden, eight paintings by the artist were on view, including four works that had originally been meant to go to St. Louis. Dresden could thus be interpreted as a kind of surrogate or alternative event for the World’s Fair in the United States. The concurrent “10th Exhibition of the Munich Secession” only received two works by Klimt: From the Realm of Death (Stream of the Dead) (1903, unknown whereabouts, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945) and Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt – Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)).

First Presentation of Water Snakes II

Having already presented his most recent works to the public in 1903 within the framework of the “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”], Klimt only showed one painting in 1904 that had never been on view before: Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection). It was on display from March to June in Room VI of the “XX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“20th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”]. This exhibition of the Vienna Secession would be the last for Klimt to participate in as a member of the association. However, according to several newspaper articles, Water Snakes II was still unfinished when the exhibition began. The painting was only delivered four days after the opening of the exhibition on 28 March. A photograph by Moriz Nähr offers a glimpse into Room VI, with the first version of the painting mounted on its walls. It is the only reproduction known to date of the unfinished work, which Klimt would extensively rework later on. The critics were rather ambivalent about Water Snakes II, but did not necessarily give negative opinions: “[B]ut as much as one seeks to fight and resist, eventually the mysterious magic of all this withering, sickly, and impossible beauty prevails.” In late 1904/early 1905, the painting was on view again at the “Ausstellung der Wiener Kunstvereinigung Secession” [“Exhibition of the Association of Artists Vienna Secession”] in the Volksgarten in Linz. Here, too, the response of the critics was largely positive:

“Had the ‘Secession’ only sent this one painting by Klimt, visiting the exhibition would still be worthwhile.”

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XX. Secession exhibition, April 1904 - June 1904, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster of the second exhibition of the Deutscher Künstlerbund in Berlin, 1905, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Exhibition of the Union of German Artists in Berlin

In May 1905, the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”] was held in the rooms of the Berlin Secession. In what would amount to the first “Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition” in Berlin, the painter was assigned a room of his own. He and Ferdinand Hodler were the only two artists to whom separate rooms had been made available. Altogether thirteen paintings by Klimt were on view. As we know from a shipping note, most of the works had been delivered by Galerie Miethke, which processed most of the sales of Klimt’s works at the time. Among the paintings was Water Snakes II from the previous year, as well as two new pictures: The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) and Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich). From information provided by the artist we know that the latter work was exhibited in its unfinished state, as is documented in the third volume of the magazine Kunst und Künstler.

As the painter’s oeuvre on view came close to the status of a solo exhibition, the Klimt Room was of special significance. Unlike the rest of the exhibition rooms, all of which were plain, the room assigned to Klimt was elaborately decorated. This interior decoration work took longer than expected. Moreover, customs problems arose when his works were delivered, as Klimt wrote on a picture postcard from Berlin to Emilie Flöge. Because of all this, his room was not yet ready on the day of the preview held for the press on 18 May, although it could then be finished in time for the official opening on 19 May. The new paintings The Three Ages of Woman and Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein were in the focus of the reviews:

“His oddities have caused some shaking of the head, above all the ‘Three Ages of Woman,’ which has been provocatively installed on the main wall [...]. The portrait of a slender young woman was particularly admired and attracted all the more attention, as the original, a Viennese married to an Englishman, was frequently present in the room.”

Picture Postcards from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna

-

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/17/1905, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/17/1905, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/17/1905, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/17/1905, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/19/1905, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/19/1905, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/19/1905, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Berlin to Emilie Flöge in Vienna, 05/19/1905, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

In the context of the Berlin exhibition, Klimt was honored by the jury. His prize included his use of a studio at the Villa Romana in Florence, which had been purchased by the Union of German Artists and which would be made available to him for an entire year. Klimt politely declined and proposed Maximilian Kurzweil for the studio instead.

1906 – An Uneventful Exhibition Year

As a result of the scandal that had surrounded his Faculty Paintings in 1905 and which had frequently been discussed in the press (following repeated criticism, Klimt had bought his way out of the contract with the Ministry of Culture and Education), Gustav Klimt noticeably withdrew from the public eye. Moreover, he and the so-called Klimt Group left the Secession. Both his reorientation as an artist and his personal retreat could have been reasons why there is merely one exhibition of Klimt’s works documented for the year in question. From January to March 1906, Galerie H. O. Miethke organized the show “Old and Modern Pictures” [“Ausstellung von Werken alter und moderner Meister”], where the controversial Faculty Painting of Jurisprudence was presented to the Viennese audience for the first time since it had been on view at the “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”] in 1903/04.

Literature and sources

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): XX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs Secession Wien. März April Mai 1904, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 26.03.1904–12.06.1904, Vienna 1904.

- Städtischer Ausstellungspalast (Hg.): Offizieller Katalog der Grossen Kunstausstellung Dresden 1904, Ausst.-Kat., Municipal Exhibition Palace (Dresden), 01.05.1904–31.10.1904, 4. Auflage, Dresden 1904.

- Verein Bildender Künstler Münchens. Münchener Secession (Hg.): Offizieller Katalog der X. Ausstellung der Münchener Sezession. Der Deutsche Künstlerbund (in Verbindung mit einer Ausstellung erlesener Erzeugnisse der Kunst im Handwerk) im kgl. Kunstausstellungsgebäude am Königsplatz gegenüber der Glyptothek, Ausst.-Kat., Royal art exhibition building on Königsplatz (Munich), 01.06.1904–31.10.1904, 1. Auflage, Munich 1904.

- Galerie H. O. Miethke (Hg.): Old and modern pictures. Tableaux anciens et modernes, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 00.07.1906–00.00.1906, Vienna 1906.

- Deutscher Künstlerbund (Hg.): 2. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes, Ausst.-Kat., Exhibition house on Kurfürstendamm (Berlin), 19.05.1905–06.10.1905, Berlin 1905.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Berlin an Emilie Flöge in Wien (05/19/1905).

- Brief der Galerie H. O. Miethke in Wien an die Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs (05/06/1905). 27.2.1.6547, .

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969, S. 339-341, S. 345-350.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903).

- Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 3. Jg. (1905), S. 398.

- Neue Freie Presse, 21.02.1904, S. 2.

- Neue Freie Presse, 29.03.1904, S. 8.

- Neue Freie Presse, 19.05.1905, S. 9.

- Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 20.05.1905, S. 9.

- Wiener Zeitung, 08.04.1904, S. 17.

- Ostdeutsche Rundschau, 26.03.1904, S. 4.

- Wiener Caricaturen, 14.02.1904.

Drawings

Gustav Klimt: Two female nudes embracing, 1903-1907, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

In 1903/04, Gustav Klimt switched to a hard, pointed pencil on Japan paper for his drawings. As he continued the theme of the underwater world, he turned to the erotic depiction of reclining women more and more. The studies for female portraits showcase frills and robes, while he prepared allegorical subject matter with naturalistic nude studies.

In 1903/04 Gustav Klimt chose to change his drawing technique and medium: Instead of black chalk on wrapping paper, he went for pencil and Japan paper. The pointed pencil left a thin, metallically sparkling, albeit barely visible trace on the paper. As a result, from 1904 onwards Klimt’s drawings came to be increasingly ethereal and precise. This reorientation went hand in hand with a more radical stylisation in Klimt’s painted work. The fine linearity and pronounced flatness of the picture space can be interpreted as equivalent to the use of gold.

In addition, he turned to erotic descriptions of female bodies: a subject the artist indulged in with a large number of drawings of half-dressed or barely dressed ladies. Connoisseurs of Klimt’s art knew that he drew pictures of masturbating women or lesbian lovers, which he used as studies for Friends I (The Sisters) (1907, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) and Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection). Regardless of this, some drawings made between 1904 and 1906 went public as illustrations for Dialogues of the Courtesans.

Gustav Klimt: Reclining semi-nude, 1904, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sleeping boy to the left, circa 1906, Detroit Institute of Arts

© Detroit Institute of Arts

Studies for The Three Ages of Woman

Klimt’s most important allegorical work of this period – The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) – was prepared by the painter with sensitive studies of arm-held infants. Several sketches of a mother-and-child motif on a single sheet, as well as the drawing style as such suggest a swift work pace. Since he made several studies of his seated aged mother during this period, it is assumed that she may have posed for the painting. The transfer sketch for The Three Ages of Woman (1904, private collection) conveys the intimate closeness of the three female figures even more intensively than the executed painting. Since the mother-and-child group is turned to the left, the mother inclines her head towards the old woman. In the transfer sketch, the latter stands in front of the young, somewhat taller mother and overlaps her hand. It seems that Klimt realized his change of plan, namely to depict the mother and child in the opposite direction in the painting, with the help of tracing paper.

Portrait Studies

Like in the years before, Gustav Klimt carefully studied the postures and especially the costumes of the ladies he portrayed in the context of his portrait commissions. The dresses, richly embellished with frills and flounces, for example in Portrait of Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Belvedere, Vienna), present a contrast to the strictly linear and two-dimensional approach to space.

Klimt tried out a variety of poses in his studies in order to effectively harmonize the cut and fall of the dresses and the postures of his sitters. It is obvious that he was only interested in the figures and the seating furniture. The drawings of seated and standing women thus allow us to conclude that Gustav Klimt only developed his sitters’ surroundings on canvas. Different from his erotic drawings, Klimt also worked with colored pencils in green and red on Japan paper.

Literature and sources

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Colin B. Bailey (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Modernism in the Making, Ausst.-Kat., National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), 15.06.2001–16.09.2001, Ottawa 2001.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012, S. 166-173.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982, S. 50-57.

- Alfred Weidinger: Die Ursucht oder die Lust am eigenen Körper. Feminine Sexualität im Werk von Gustav Klimt, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jane Kallir, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 22.10.2015–28.02.2016, Munich 2015, S. 30-47.